It's not startling like an explosion; it's startling like the way life is: gradually growing on you how great things can really be, until it explodes in your head and you are happy to have existed. Which is weird because it's also a very sad book, in many respects.

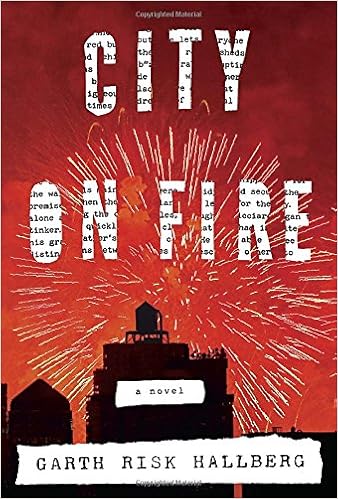

It is a book about New York City in the 1970s, mostly, and mostly means "on the surface" there. It's a book about suburban kids getting in over their heads, would-be anarchists becoming real anarchists, rich people and their rich people problems, and, weirdly, a book, too, about fireworks.

It's a book that is overwhelmingly long; I want to say it was 3,000 pages, but that's probably not technically accurate. Amazon lists it at 944 pages, but it could have gone on for far longer and I doubt I would have minded.

It is a book that is all-encompassing, creating an entire world that is so real. That the book feels real is odd, in a way, because the characters are at the same time stock characters but somehow also realistic, maybe because they are so stock-characterish that they come full circle and move past that.

It's a book that in the end is almost mystical about how life works out, with resolution by, if not God, then some other machina of the deus. It has endings that for the most part are happy, if you forget all the things that have happened so far.

It's a book that I want to read again, and probably someday I will; it's already earned a spot on the list of favorite books in my entire lifetime, and I only just finished it the other day. In this case, I didn't wait to write it up because I was tired; I waited because I wanted to finish absorbing it.

Other review of the book have compared it to Dickens (which I get, maybe a little, only in spirit, though), and to longform TV shows like The Wire (never watched it, never wanted to). I think the book it's closest, too, though, is Bonfire Of The Vanities, with which it shares a lot of stock situations, as well, and which is similar in its intent and ambition.

Here is what I can muster as a summary of the plot(s) of the book: in general, each of the many, many characters -- some of whom are essentially offstage until they show up for a brief starring turn -- is touched on as they revolve around, or build up to, New Year's Eve 1976 and the 7 months that follow it. There is a thing that happens on New Year's Eve; to say what happens would ruin what that thing is, and so I won't. This thing is both the culmination of, and progenitor of, most if not all of the other events in the book, many of which are in their own way as much a turning point or major event, also. (One of the possible themes of the book is that turning points are what we think they are. There are enough major events happening to all the characters to make it hard to pick which one is the pivotal point in their life. One character is adopted, has his father die, falls in love, has a religious experience, and gets hooked on drugs -- and yet none of those things seems as important, in this character's arc, as the attendance of a rock show at a club on New Year's Eve.)

That brief skeletal summary is hardly enough to do justice to a book that traces its characters back to 1950, and spans New York, San Francisco, Georgia, and Scotland, so here's a bit more: the main characters in the book are all connected in some way. There is Samantha, a 17-year-old who has just started college in New York, and who likes taking pictures of graffiti, trying to be punk rock, and hanging around. Sam is adored by Charlie, an adopted kid also from Long Island who loves her with the desperate kind of crush that only a 17 year old can have -- he shaves his head into a mohawk and swipes the car to go visit her at one point -- and Sam and Charlie hang around Nicky Chaos and his group of "PostHumanists," a sort of mixup of punk rockers, would-be philosophers, and anarchists that include members of Charlie and Sam's favorite band, Ex Post Facto.

That band, meanwhile, was started by "Billy Three Sticks," who is also known as William Hamilton-Sweeney III, the estranged son of a millionaire financier; Billy's sister Regan and her husband Keith and their kids have big roles in the book, as well.

I could probably keep going. There's enough plot to keep everyone happy, and it all overlaps in these big swoops of storytelling. But there are other things to discuss with the book, whose richness goes beyond simply an engrossing story populated with people that are interesting to follow around. The book is a masterpiece, if you ask me, in so many ways, and can be thought about in so many ways.

First, there's the way I read it. I originally got the book as a digital loan from the library. You only get those for three weeks, and I was only on about page 400 when the loan expired. That alone is remarkable: I do not read quickly, and 400 pages in three weeks is a major commitment for me. When I requested the book again, I was something like 5th in line, which could mean as much as three months before I get it back, and I couldn't wait, so I took the book out in hardcover from the library. Because it was on a special list of the best-sellers, I only got that version for two weeks; a week in, I requested a copy from another library, so that when the first 2 weeks expired, I got the book a third time.

That's a demonstration of how enjoyable it was to read this book. Over the five weeks that I read it, it slowly took over from almost all other reading, until by the final week I was skipping reading news stories and not watching any television just to read this book. And when it ended, when all the mysteries were solved and plot lines tied up -- some in fantastic fashion -- I didn't want it to be over.

That's the other thing about the book: it's somehow not enough. A few reviews I read said that Halberg cut some 200 pages from the book, and I can't figure out why. Hopefully they were cut because they weren't any good, although that's hard to conceive; a book this skillfully done is not likely to have nearly 1/6 of its original volume be deadweight, if you ask me.

I remember when I read The Stand, I read the author's cut, and King explained that the originally-published version had been edited down to meet some sort of arbitrary criteria. (According to Wikipedia, the publisher thought people wouldn't read the 1,152-page version, so King cut out 400 pages -- 1/3 of the total! -- to make the book more marketable.) You'd like to think that with longform television series, and even longform movies -- Kill Bill and The Lord Of The Rings and now the Marvel and DC Universes -- coming out, publishers would trust readers to buy a book regardless of its length, if it's good. (And that, again, is a reason why electronic publishing is generally better than paper-books: you don't have to worry about shipping and production costs in an ebook, and you don't have the problem of holding a giant book that weighs like 10 pounds as you try to read in bed at night). Maybe someday I'll read City on Fire the way Hallberg intended it to be read, if in fact the 200 pages were ones he wanted but was forced to cut.

Then there is how long the book took to write, and what Hallberg says he was trying for. He says it took him five years to write, after thinking about it for 9 years before that. Hallberg is I guess a book reviewer who has only written this novel, which is all the novels anyone could be expected to produce in a lifetime, especially when that one is this good. (I hope it's not his only one; I hope he writes more brilliant stuff.) Hallberg said in an interview he wanted to be Dom DeLillo-esque, which is a very literary goal: most people would, I think, say they wanted to be an author that is recognizable outside of the literary world. I read DeLillo's book about the baseball (Underworld), which was picked as the best book of the previous 25 years back in 2006. I kind of remember it? I think? Anyway, I don't think Dom DeLillo has the kind of general acclaim that other esteemed authors might, and picking DeLillo might be the authorial equivalent of when someone says "I don't own a TV," but after having read the book, I kind of think Hallberg is sincere: I think he wanted to write something serious, something that would resonate and be around and be thought about, as opposed to something that would instantly grab popular acclaim and then (maybe) fade. (For what it's worth, the book grabbed popular acclaim right away, with a $2,000,000 advance, one of the largest ever for 'literary' fiction, and the movie rights were sold to about a zillion countries and studios before it was published, too, so it's not like Hallberg scorned popularity.) I think the point of Hallberg's ambition was to write a book he wanted to write, not a book we might want him to write, and I think he did that.

(I might be sympathetic to that point of view; I have been working for several months now on a new book, one that is only about 1/4 done and which might well take me a year or two to knock out, because I am trying something new for me, something that now has been influenced by the realization that books like City On Fire are possible: big books that think about lots of things.)

(The publisher, asked about lackluster sales, said "This is a book we want people to be reading in 20 years." I think maybe they will be?)(Then again, the real way to last a long time is to write genre fiction, as the secret of longevity is mostly popularity: if a lot of people liked you, you will be fondly remembered and passed on to generations, rebooted, revisited, and reworked. Ask Shakespeare, or Tolkien, or William Shatner, about the relative merits of "literary" versus "popular." William Faulkner never got to do Priceline commercials.

Not every reviewer liked City On Fire, and it didn't rise very far up the best seller lists. The publisher gave away 6,500 copies, and a few months after it came out it had sold 75,000 copies -- which would've been about 225,000 copies short of making any money for the publisher. Some people hated it; most people compared it to the same things I've compared it to: television series that delve into characters in depth, or Dickens. Only a few articles about the book link it to The Bonfire Of The Vanities, which, like I said, was the book it reminded me of, especially in the early going. Both books deal with the intersection of money and poverty, both involve a crime and an investigation, both have a reporter with a bit of a drinking problem -- is there any other kind, in books? -- and both are vast in scope. But they're like mirror images of each other in another respect.

Bonfire of the Vanities captured, like a butterfly pinned to a board, the 1980s perfectly. It took a vast, overarching moment in the culture, the 1980s, and encapsulated it, boiling the questions of that era -- questions that were mostly buried beneath a sheen of Reagan's Morning In America, the glow from the sun blocking our view of illegal arms sales and the institutionalization of trickle-up economics beginning the long decimation of the middleclass-- down to the essence of what was being fought out then (and now, still): rich versus poor, black versus white, men versus women, the power of the law and the power of money. Bonfire took a vast sprawling decade (one that still looms over America more than perhaps any other in the past century) and, despite setting the story in New York with a giant cast, made everything feel minute, personal: from the feel of the sweat under Sherman McCoy's collar to the way styrofoam peanuts clung to his pants to the peculiar glare of lights in Tommy Killian's office, it was a perfectly-detailed book in which the players almost became archetypes. Bonfire was a novel the way Greek plays were plays: everything was layered over with meanings, everything symbolized something about the way we, as Americans, lived in that particular moment of our existence.

City On Fire shares the eye for detail and transmission of the sensual about the characters' experience: it's a visceral novel in how it feels, and reading it is like being on (what I imagine) New York streets in 1976 or 1977; reviewers have called it cinematic, and it is: there is no detail too small for Hallberg to communicate, and rather than bogging down the story, it makes the story feel real. But beyond that, City On Fire looks outward, asking us where we are now in comparison to then; Bonfire pulled everything in and said this is this moment: this is now. Fire takes a moment in time (two, or three, actually: the Bicentennial, New Year's Eve, 1976, and the blackout in 1977) and explodes them outward, holding them up as a mirror to what has happened since then, how we got from there to here. It's like reverse nostalgia; instead of saying oh yeah I remember that cool, we look and say oh man that's how this became that.

(One critic asked "Why is the book set in 1977?" That's a silly question. Why is Star Wars set in the past, in space? Why is The Tempest set on an island or something weird [never read it]. It's set there because that's when Hallberg set it there, but if you read the book while actually thinking about the book, you can see that the setting of the book in that place, in that time, matters: it was the last time New York could be described as both wild and somehow accessible: by the 1980s, New York was a crime-ridden crack den, and by the 1990s it was a Disneyfied playground for celebrities. New York has followed America's path over the last forty years; it has reflected our recession, as a people and a society and an idea, into something less great, something where the real divides are papered over with fake culture wars foisted on us by political parties that are for all real purposes the same party, something where branding and marketing is so prevalent that we expect it, and welcome it, and defend it when some question whether perhaps we should not be engrossed by Kim Kardashian's literally-made-for-tv-melodrama. Hallberg's 1977 New York might well be the people we used to be, before we were DraftKinged into submission and left sitting on our sofas with 'microbrews' created by international conglomerates, bemoaning the fact that the two candidates we picked for President are in fact the two candidates we picked for president. The book is set in 1977 because Hallberg's America wanted to point a finger at an America where someone could be a literary critic and ask 'why is the book set in 1977' and still be taken seriously.)

The book echoes 9/11 -- there may be a bomb, and it may be in a building, and the building is a center of commerce -- and talks about cheesy Bicentennial celebrations, and has cops going through both stereotypical motions and unique gestures; it has a demonstration that turns into a blackout that turns into a riot. It has misbehaving capitalists and insider trading and the failure of the American city and everything turning into money. City On Fire takes all of these things: bombs, murder, police, race, sexuality, art, vandalism, youth, divorce, criminals, and treats them as the headwaters of American culture now; there is a feeling that the book, despite being determinedly set in 1976 and 1977 for the most part, there is still a feeling like the book has somehow been 'ripped from the headlines,' as it were, and the headlines are not 40 year old musty newspapers but instead are the Yahoo! emails some people still for some reason get in their inboxes, because searching for news on the Internet is hard.

There's a sense, in City On Fire, of a world on the edge of being out of control, of things going off the rails, of everyone ending up badly, and that sense is thrilling to someone like me, like us, who in fact live in another time where things feel like they're about to explode. There are a lot of similarities between the 70s and the 10s: coming off a decade of war, coming out of a financial struggle, racial troubles and leaders who don't seem able to cope and who aren't trustworthy, a shaky new world where the alliances and enemies aren't always clear, a culture that is badly divided and needs to find a way to work together, or at least coexist. It's that sense, too, that City On Fire reminded me of Bonfire Of The Vanities: it captured the moment in which it was born, perfectly -- even though City doesn't pretend to be set in 2016, but thirty years earlier.

Catch-22 is my favorite book in part because I so often think the world is absurd, because we can't always tell who our real enemies are, because it's hard not to see goals as arbitrary and somehow still receding in front of us, hard not to feel perhaps that there are powers toying with us for their own purposes that, when we comprehend them, will be sad and petty.

Rabbit, Run grabbed at the parts of me that wonder how we ended up in this life -- not the parts of the life we chose, but the parts of life where those were the only choices we ended up having -- and helped me understand the good, and bad, ways of dealing with a lack of choice, and understanding what each is.

Those books, and others, helped encapsulate a way of looking at the world, helped make sense of complicated thoughts I had. Books as therapy, as confessional, as friend -- and that's not such an unusual thought, given the amount of time we spend reading a book; starting a book is like starting a relationship, and ending one is sometimes the same sort of thing. City On Fire worked on me on a different level than those, though. It did not mark some sort of emotional or intellectual breakthrough; I did not think Oh, that's how the world is when I read it.

When I was 16, I first heard songs by a rock group called The Violent Femmes. The Femmes sang about alienation and anger and loneliness and being misunderstood and exploding out of one's surroundings to do something. As a 16 year old, I ate it up, even though your average suburban middle class teen (me) is about as alienated and misunderstood as a Golden Retriever; never mind that, though, teens feel that way, or want to feel that way at least part of the time, and the music made me feel like if I was that type of person, someone would understand me. Even now, at 47, when I listen to it, I can feel the same sense of wanting to be misunderstood, a bit, and alienated, a bit, and lonely, a bit -- and at the same time wanting to feel those things but also feel like hey, these guys, they get it, they know how I am.

That's the kind of feeling I got reading City On Fire. Nearly every character, every storyline, every plot twist: It felt like hey these guys, they get it, they know how I am. I felt like I was reading a story about people like me grappling with the same kinds of ineffable forces I feel as though I struggle with. They might have their Demon Brother (if I have a quibble about this book, it is that the Demon Brother did not live up to the hype his name foretold, although maybe that was intentional?) and their psychological quirks and their drug trips and their religious fervor; but I have similar foes and similar ideas and similar beliefs to cope with, and even if they aren't the same, they're kindred spirits. Their struggles were proxies for the struggles we all feel.

It's a book that I, at least, needed to exist, and I'm glad it does.

2 comments:

I spend my life in "misunderstood." And, mostly, I don't even try to explain, well, anything to anyone, anymore, because, after 40 years of it, what's the point?

But I probably won't read this book. Not because it doesn't sound interesting, just because it's unlikely that I'll pick it up. Maybe if I had read Bonfire (or even seen the movie), I would have a greater desire to do so, but I haven't so I don't.

Part of me feels bad for that.

Eh. I stopped feeling bad about books I won't read. Too many to keep up with. I don't think this is necessarily a book for everyone. But if you get around to it it's worth reading.

Post a Comment