Mr F doesn't like libraries, but Mr Bunches and I do, so when we want to go to a library, we usually try to do something for Mr F first, like go to a park or go swimming or something. Today we didn't really have that chance. It was raining, so we couldn't go outside and play, and we all went swimming last night, so as a warmup for Mr F to go to the library, we went to "Rocket McDonald's," which is a McDonald's that has a playland with a big spiral staircase thing that for some reason we decided looked like a rocket. (It doesn't.)

Mr F wasn't crazy about that either: he seemed spooked by the rocket-stairs, going to them repeatedly and then climbing up one before skittering away. He spent much of the time hanging out by his french fries or sitting in the high chair.

So when we went to the Verona library -- the next town over, and a library I've wanted to go to for a long time because from outside it looked really spectacular -- I decided not to follow my usual routine with Mr F, which is to pick out a book and make him read it with me. Since Mr Bunches plays with all the library toys and then reads all his books before we go, Mr F is usually stuck at the library for a pretty long time, so we walk around and look at the books and check out the movies and the bubblers and the art and etc., and then we sit and read a book together, and then we just hang out until Mr Bunches is done.

Today, like I said, I didn't want to make him read, since he already was out of sorts. So I decided I'd read to him, and was looking around for a book when I came across Book 32.

What really attracted my attention to it was Neil Gaiman's name being on it. I'm not sure what I think about Neil Gaiman. He wrote one of my all-time favorite books (American Gods) but I thought The Ocean At The End Of The Lane was only so-so, and I gave up on a collection of his short stories. I liked Coraline as a movie. But I've also gotten the feeling that Neil Gaiman is getting all kinds of credit just for being Neil Gaiman, the way Stephen King can just write anything and it's going to sell a billion copies.

So I wasn't entirely sure that Neil Gaiman writing a kids' story would work. It was entirely possible that this was just a way to boost sales for some book, pasting Neil Gaiman's name on it, or that it wasn't one of his best. But I decided to give it a shot.

The way we did it was Mr F would sit somewhere -- the castle, a chair, the slide -- and I'd sit by him and read it quietly to him. If it got too crowded around us we'd move to a quieter spot and continue. It's hard to tell if Mr F is paying attention or not, but I figure at least hearing the reading is worth something.

The book was actually really very good -- and surprisingly so, I think. Everyone knows the story of Hansel & Gretel: two kids led into the woods by their dad who stumble across a witch's cottage and end up shoving her into the oven. What Gaiman did here though was flesh out the story (to be fair, I don't know how much of the original Brothers Grimm story there was, so maybe he just rewrote it?) to give some dimension to the characters, and add some emotional complexity. In the end, he wrote something that's more than a book for children, and is actually quite chilling if you think about the story.

The story here has the mom convincing the dad to take the kids into the woods because there's a war, and money and food are scarce, and they won't all survive -- so two can die so that two can live. Hansel overhears them talking and the next day he's ready, with white stones in his pocket to trace their way back. So the first time it doesn't work, but the second time Hansel isn't ready, so he has to leave bread crumbs, and of course they get eaten, so they wind up at the cottage, where the witch is pretty gruesome, referring to Hansel as meat and trapping him in a cage.

What really makes the story work better than just a fairy tale is both the extra time dumping them in the woods, and the little details that show Gaiman at his eerie best. The first time they go out, Hansel knows what's up but Gretel doesn't, and Gretel (the elder) seems to not want to believe their dad just dumped them in the woods. But the second time it happens, they both know what's going on. That leads to this:

Gretel's getting it was a really creepy moment, as was the witch's house, with Hansel being fattened up in the cage. To keep the witch (who is almost blind) from realizing how fat he's getting, Hansel takes an old bone that was lying in the cage, and each day when the witch comes in to feed him and says to poke a finger through the bars so she can see how fat he's getting, Hansel pokes the bone through, tricking her into delaying until she loses patience and has Gretel build a fire in the stove to cook her brother anyway. When Gretel goes to get her brother out, having burnt the witch, she wonders why Hansel clings to the bone and won't let it go, and anybody reading it should get a lump in their throat at that.

After I read it, I was thinking about how for kids it's a pretty scary story: what's scarier than being abandoned by your father in the woods, and then taken in by a witch? The contrast between the woodsman's sparse larder and the witch's gingerbread house only makes the comparison more stark: why wouldn't the kids think the witch was nice? But, it turns out, no adult is to be trusted, from a kid's perspective: parents will dump you in the woods and strangers will cook you and eat you.

Reading it as a parent, though, I got a whole different perspective on it. The mom's choice is horrible (I'll have more to say on that below) and the dad's decision to go along with it just as bad, but how bad would it be if you couldn't provide for your kids and knew they would end up starving? I think any parent would say the kids should get the food and would do everything they could to make sure the kids live, but what that leads to in this case is (unless the war in the story ended real soon) two kids with dead parents living in a wartorn country stricken by famine.

I think there's little worse, from a parent's perspective, than letting a kid down, or feeling helpless in the face of adversity. I feel terrible everytime we have to limit Mr Bunches' toy budget; but we're not made of money and he'd bankrupt us if he could, so the lesser evil is to deny him the many requests for toys he makes each day. I felt worse the night Sweetie and I sat up all night in a dark hospital waiting room while Mr F had brain surgery. I remember being exhausted and wanting to just lie down for a minute or two, around 4 a.m., but every time I thought about that I would picture Mr F in the operating room. I couldn't do anything for him; I'm not a brain surgeon and there wasn't anybody to sue. So I did the one thing I could do: I stayed awake, trying in some way to at least be in the same boat with him in whatever way I could: while he was going through whatever he was going through, I was forcing myself to have some tough times.

It's that feeling, in good parents, that makes kids love us and makes us a good parent: the absolute certitude that we would take any amount of harm or danger or trouble if it would spare kids from some problem. But what about when there is no good option, only bad and worse? I was walking around looking out the windows with Mr F thinking of what the parents could do, how they might have tried to get to a different country, or worked to catch more animals or something. But each day they'd realize their kids were hungrier and hungrier and would simply have to hope that things get better.

It's that feeling of helplessness I think would be the worst. The hardest times for me in my life are when things are out of my hands: pacing around the hospital waiting room, or when a jury has gone to deliberate. You simply sit and think about what you could have done, how things might have been even a bit better. I imagine that's the desperation Hansel & Gretel's parents felt -- but the choice they made makes them, to me, every bit as bad as the witch. She was going to eat them to stay alive, but the woodsman and his wife sacrificed the kids so they could live. You could argue that the witch was doing what witches do: is it evil to give in to your nature? But the parents? Parents don't kill their kids so they can live longer.

That's why the ending of the book was hard for me to take. Hansel & Gretel escape, of course, and they find their way back to their parents' house, where their dad is waiting. They're excited to see him and they've brought all sorts of diamonds and gold from the witch's stash, and as their dad hugs them they ask where their mom is. She's died, and Gaiman suggests that maybe the Mom died because she missed her kids.

I suppose it might be natural for kids to love their parents. All kids want to think their parents are loving and great, and will go to extremes to justify behavior that is bad, or worse. Kids make excuses for terrible parents all the time. (I see some of it in my job.) But at the end of the book, the dad has paid no price whatsoever, really: he dumped his kids in the woods, they were captured and nearly eaten by a witch, and they bring him back riches and they all lived happily ever after and never wanted for anything again.

WHAT KIND OF MESSAGE IS THAT? I know this was a kid's book, but it was a kid's book where the author felt it was okay to refer to kids as meat, and then it just cheaped out in the end, with a sort of "oh well your dad loved you he tried his best," which, after the 99% of the book that was really far better than a retelling of a fairytale could be expected to be, was a colossal letdown. I would have had Hansel and Gretel make their way to another town, and live off their riches. Or stay in the witches' gingerbread house and help travelers who are lost, until they were old enough to go back to civilization. Something like that would've been a more consistent story, I think: Hansel & Gretel could only trust each other, after the entire world, so far as they knew, treated them as disposable. Why not tell kids hey if people treat you bad you just leave 'em behind? Gaiman ends up with a "they all lived happily ever after even the dad who, after all, only dumped his kids in the woods twice so that he could live while they didn't, and then never even went searching for them," and it feels like a cop-out, as if he realized the book was due in a half-hour and had to get something on paper, or he was worried about pro-dad groups pestering him. (Pro-dad groups -- mad dads -- are the worst. They are horrible people.)

I wasn't going to count the book originally but it actually made me think more than some of the other books I've read, so I threw it on the list.

(PS the artwork in the book is phenomenal and guaranteed to spook kids.)

Saturday, April 30, 2016

Friday, April 29, 2016

15,842 New Words: I probably should have looked up 'Carpathian' too.

“I’m only going to say this once, so don’t fly off the handle,” she said. “Flax Hill is home to me because I loved Leonard Fletcher. Not the other way around.”

“Right, but I’m not trying to— Arturo’s not— the air tastes of palinka, you see,” I said, idiotically. “Here in Flax Hill, I mean.”

Boy, Snow, Bird: A Novel, Helen Oyeyemi.

Palinka is a traditional fruit brandy invented in the Middle Ages, coming from the Carpathian region, which so far as I can tell is Hungary and parts of Austria.

I mean I don’t know if this word will be helpful in my everyday life but I like it.

Thursday, April 28, 2016

Book 31: Even though I loved this book very much I had to keep looking up the name to remember how it went each time I talked about the book.

It's hard to know what to say about In The House etc etc. The book is a nightmare, but in a good way, if that's possible.

There are a few books I've read that I think are not like any other book, or like each other. A Short Sharp Shock was one. 100 Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses was another. Foucault's Pendulum, and The Rathbones were a couple of them. When you happen on one of these books, it's like turning over a rock or standing on your head and looking at your backyard or driving through a thunderstorm or maybe all three of those things at once: books like this reveal something, look at things differently, attack everything around you violently even as you sit, sheltered, away from the maelstrom.

When I was a kid, when I was like 14, I had a nightmare. I remember it now, more than three decades later. In the nightmare, I was running down a snowy hill, through pine trees. The snow wasn't deep; it was only up to my ankles, and served more as a slight impediment and a way of blurring out the scene. I kept running and running . It wasn't one of those dreams where you can't move or you never get anyway. Quite the opposite: I ran fast, and a long way, looking over my shoulder all the time to try to see whoever was chasing me. At one point, though, just as I turned back to look where I was heading, a man in a ski mask leaped out from behind a tree and stabbed me in the side.

I woke up, instantly. I didn't feel scared. I wasn't breathing heavily, or sweating, and hadn't screamed. I was just, instantly, and completely, awake. I went down the hall to the bathroom to get a drink of water, and turned on the light. It was only then that I realized I was holding my hand over my side, right where I'd been stabbed, in the dream. I kept looking at my hand in the mirror, telling myself it was okay to take my hand off, that it had only been a dream, but I didn't, for a long time, and then when I finally did move my hand, and saw only unbroken skin, I let out a huge breath: I'd been holding my breath as I wondered what I would do.

That dream remains crystal clear to me even now, an unreal experience that I can recall every detail of, right down to exactly where I held my hand.

In the way a dream like that can stick with you and taunt you with what your subconscious is thinking about, in the all the subtle ways a completely fictional experience can shape your perceptions of yourself and your world: that is how In The House... affected me.

It's not an easy book to read, In The House... and not a comforting one. But I'm glad I read it. I don't know that I'd ever read it again; in that way the book is like my visit to the Holocaust Museum: an experience I feel like I should have, but not one I'd want to repeat.

All that said, it is an excellent excellent book. It is a book that I think deserves to be far more widely known than it is already, because people should know that storytelling this powerful and unsettling exists. It's a book that opens up a new possible.

The plot of the book is sort of secondary, and doesn't do the book justice. In a nutshell, a man and a woman -- they're never named, although hints about the woman's name are given and made me think maybe I was right about this being, in part, a retelling of a bible story -- move to a wilderness area, between a lake and the woods. They plan to raise a family and live there alone, but events overtake them and the resultant story is both fantastic and terrible in its unfolding.

That mundane description, though, doesn't explain the poetry of the book, both in the language used (Matt Bell is a wonderful writer) and in the way the world acts around the man and the woman, and the way they act. The woman can sing things into existence, while the man, cruder, must build and hunt and trap. Their efforts to have a family eventually tear into their relationshp, causing the woman to wreak havoc with reality, while the man has run-ins with a bear and a monster in the lake.

From there, the story gets ever more compelling and more extraordinarily irrational. It would spoil too much to say what happens, but stars fall from the sky, there is a phenomenal showdown between the man and the various beasts, a descent into almost-literal madness, and the creation of whole new worlds within other worlds. It's amazing.

It's also very, very dark. It's like the Brothers Grimm decided to retell all the scariest stories humanity has ever come up with, or like Edgar Allan Poe's fever dream. It was a book that I read only in short sittings; after 30 or 45 minutes I had to come up for air and do something else for a while.

It's not a book for everyone. It's a real challenge, reading it, but each page is more compelling than the last. The story just kept getting better and better, more and more astonishing, and each time I thought okay we're on our way back down now things just escalated even more to greater heights... or depths, I guess, as large parts of the story take place underground in the 'deep house' or even lower, below a giant staircase that descends so far into the earth that time actually stops meaning anything for a while... until the story comes to an ending rather abruptly, in a way that makes perfect sense.

I think it's very much worth trying to read it. If you get two or three pages into it, you'll either not want to stop or will give it up right away; it's that kind of a book. It's totally worth it, though. I don't think I'll ever forget the bear, and the lake monster, and the children... oh man, the children! If you thought kids in movies like Children of the Corn or Goodnight Mommy were freaky, wait until you get to the part in this book where there are hundreds, if not more, children of varying shapes and sizes keeping the man from entering the woods and attacking each other and singing, each, a single note of a song over and over. Images like that will stay with me for a long, long time. Maybe forever. I can sit here and remember the arc of the story, the lake battle, the descent and subsequent ascent through the deep house, and feel a sort of dread. It's not a bad feeling in a sense: reading books like this is the modern equivalent of a Grimm story or Beowulf. It's a way of connecting to a more primal feeling within us, the subconscious that makes us who we are even when we don't understand why it is doing so. In digging up dreadful images and descrescendoes of terror, remorse, and guilt, a book like this reminds us of the darkness our lives could be, and makes you more grateful when you look up from it and realize you're not in a house made up of rooms each of which has one thing in it, and that one thing is a mockery of what life should be. No, you're in your own house where nature is not a terrifying set of half-dead animals rising from their graves, where children do not need to be sung into proper shapes. Reading this book is a journey into elemental forms of emotion that you surface from like a kid diving as far down as he can in a deep cold lake only to swim to the surface as quickly as he can to make sure the sun still exists and he can still breathe.

I don't think I'll ever forget it. I don't think it's the kind of book you can forget. I'm not sure I'd want to, though, even if I could.

There are a few books I've read that I think are not like any other book, or like each other. A Short Sharp Shock was one. 100 Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses was another. Foucault's Pendulum, and The Rathbones were a couple of them. When you happen on one of these books, it's like turning over a rock or standing on your head and looking at your backyard or driving through a thunderstorm or maybe all three of those things at once: books like this reveal something, look at things differently, attack everything around you violently even as you sit, sheltered, away from the maelstrom.

When I was a kid, when I was like 14, I had a nightmare. I remember it now, more than three decades later. In the nightmare, I was running down a snowy hill, through pine trees. The snow wasn't deep; it was only up to my ankles, and served more as a slight impediment and a way of blurring out the scene. I kept running and running . It wasn't one of those dreams where you can't move or you never get anyway. Quite the opposite: I ran fast, and a long way, looking over my shoulder all the time to try to see whoever was chasing me. At one point, though, just as I turned back to look where I was heading, a man in a ski mask leaped out from behind a tree and stabbed me in the side.

I woke up, instantly. I didn't feel scared. I wasn't breathing heavily, or sweating, and hadn't screamed. I was just, instantly, and completely, awake. I went down the hall to the bathroom to get a drink of water, and turned on the light. It was only then that I realized I was holding my hand over my side, right where I'd been stabbed, in the dream. I kept looking at my hand in the mirror, telling myself it was okay to take my hand off, that it had only been a dream, but I didn't, for a long time, and then when I finally did move my hand, and saw only unbroken skin, I let out a huge breath: I'd been holding my breath as I wondered what I would do.

That dream remains crystal clear to me even now, an unreal experience that I can recall every detail of, right down to exactly where I held my hand.

In the way a dream like that can stick with you and taunt you with what your subconscious is thinking about, in the all the subtle ways a completely fictional experience can shape your perceptions of yourself and your world: that is how In The House... affected me.

It's not an easy book to read, In The House... and not a comforting one. But I'm glad I read it. I don't know that I'd ever read it again; in that way the book is like my visit to the Holocaust Museum: an experience I feel like I should have, but not one I'd want to repeat.

All that said, it is an excellent excellent book. It is a book that I think deserves to be far more widely known than it is already, because people should know that storytelling this powerful and unsettling exists. It's a book that opens up a new possible.

The plot of the book is sort of secondary, and doesn't do the book justice. In a nutshell, a man and a woman -- they're never named, although hints about the woman's name are given and made me think maybe I was right about this being, in part, a retelling of a bible story -- move to a wilderness area, between a lake and the woods. They plan to raise a family and live there alone, but events overtake them and the resultant story is both fantastic and terrible in its unfolding.

That mundane description, though, doesn't explain the poetry of the book, both in the language used (Matt Bell is a wonderful writer) and in the way the world acts around the man and the woman, and the way they act. The woman can sing things into existence, while the man, cruder, must build and hunt and trap. Their efforts to have a family eventually tear into their relationshp, causing the woman to wreak havoc with reality, while the man has run-ins with a bear and a monster in the lake.

From there, the story gets ever more compelling and more extraordinarily irrational. It would spoil too much to say what happens, but stars fall from the sky, there is a phenomenal showdown between the man and the various beasts, a descent into almost-literal madness, and the creation of whole new worlds within other worlds. It's amazing.

It's also very, very dark. It's like the Brothers Grimm decided to retell all the scariest stories humanity has ever come up with, or like Edgar Allan Poe's fever dream. It was a book that I read only in short sittings; after 30 or 45 minutes I had to come up for air and do something else for a while.

It's not a book for everyone. It's a real challenge, reading it, but each page is more compelling than the last. The story just kept getting better and better, more and more astonishing, and each time I thought okay we're on our way back down now things just escalated even more to greater heights... or depths, I guess, as large parts of the story take place underground in the 'deep house' or even lower, below a giant staircase that descends so far into the earth that time actually stops meaning anything for a while... until the story comes to an ending rather abruptly, in a way that makes perfect sense.

I think it's very much worth trying to read it. If you get two or three pages into it, you'll either not want to stop or will give it up right away; it's that kind of a book. It's totally worth it, though. I don't think I'll ever forget the bear, and the lake monster, and the children... oh man, the children! If you thought kids in movies like Children of the Corn or Goodnight Mommy were freaky, wait until you get to the part in this book where there are hundreds, if not more, children of varying shapes and sizes keeping the man from entering the woods and attacking each other and singing, each, a single note of a song over and over. Images like that will stay with me for a long, long time. Maybe forever. I can sit here and remember the arc of the story, the lake battle, the descent and subsequent ascent through the deep house, and feel a sort of dread. It's not a bad feeling in a sense: reading books like this is the modern equivalent of a Grimm story or Beowulf. It's a way of connecting to a more primal feeling within us, the subconscious that makes us who we are even when we don't understand why it is doing so. In digging up dreadful images and descrescendoes of terror, remorse, and guilt, a book like this reminds us of the darkness our lives could be, and makes you more grateful when you look up from it and realize you're not in a house made up of rooms each of which has one thing in it, and that one thing is a mockery of what life should be. No, you're in your own house where nature is not a terrifying set of half-dead animals rising from their graves, where children do not need to be sung into proper shapes. Reading this book is a journey into elemental forms of emotion that you surface from like a kid diving as far down as he can in a deep cold lake only to swim to the surface as quickly as he can to make sure the sun still exists and he can still breathe.

I don't think I'll ever forget it. I don't think it's the kind of book you can forget. I'm not sure I'd want to, though, even if I could.

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

Sunday, April 24, 2016

The latest thing wrecking your childhood is the new Cracker Jack bag without prizes.

Just to be clear: nothing, after the fact, can ruin your childhood. Your childhood is in the past, immutable, altered only by your own perception of it.

The future, marching forward in ways you do not understand and do not want to take part in, does not wreck your childhood. But refusing to accept change can wreck your adulthood.

In other words, putting Cracker Jack in a bag and taking away the prizes, while also altering how the boy and his dog are drawn, is neither an "affront to baseball fans" nor an "affront to American innovation," contrary to what this writer bemoans in an article on Gizmodo.

What's remarkable about this article is how little thought or research went into it. The article complains about how the "prizes" in Cracker Jack are "now" QR codes to access apps on a phone. This began in 2013, 3 years before the writer had a conniption about it. That last article appeared in Huffington Post in 2013, and also noted that the company was introducing new forms of Cracker Jack, including one with unsafe levels of caffeine.

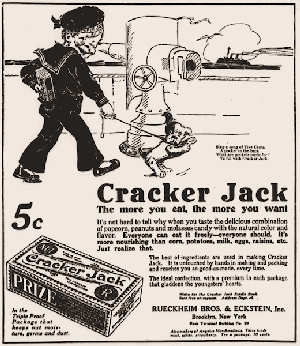

Sailor Jack and the dog were not icons for the first 20 years or so of Cracker Jack's existence; same with the toys. Both were innovations two decades in, so removing them entirely would be far more in keeping with the snack's history. They've not always been the consumer-friendly young lad and the rescue dog:

Meanwhile, this article from 2009 says Cracker Jack was being sold in bags already back then, so the affront to American innovation and baseball is older than the Gizmodo article, which is an affront to journalism. (Even more of an affront? Gizmodo's writer probably just cut-n-pasted the news from sites like Today and CBS News. Hip'n'trendy writing notwithstanding, Gizmodo is just a news aggregator like HuffPo.)

As for "American" innovation, "Cracker Jack" was developed by a German who came to America, bought out his partner and brought his brother over from Germany. The brand's roots as a snack first presented at the World's Fair in 1896 is likely a lie. the inventor of the packaging lived in Ontario -- not a part of America! -- at the time of his death.

Changing a box, a prize, an ad, a logo is not an insult to America, or baseball. But pretending that 3-year-old news copied from another website is original thought is an insult to me.

The future, marching forward in ways you do not understand and do not want to take part in, does not wreck your childhood. But refusing to accept change can wreck your adulthood.

In other words, putting Cracker Jack in a bag and taking away the prizes, while also altering how the boy and his dog are drawn, is neither an "affront to baseball fans" nor an "affront to American innovation," contrary to what this writer bemoans in an article on Gizmodo.

What's remarkable about this article is how little thought or research went into it. The article complains about how the "prizes" in Cracker Jack are "now" QR codes to access apps on a phone. This began in 2013, 3 years before the writer had a conniption about it. That last article appeared in Huffington Post in 2013, and also noted that the company was introducing new forms of Cracker Jack, including one with unsafe levels of caffeine.

Sailor Jack and the dog were not icons for the first 20 years or so of Cracker Jack's existence; same with the toys. Both were innovations two decades in, so removing them entirely would be far more in keeping with the snack's history. They've not always been the consumer-friendly young lad and the rescue dog:

|

| Pretty sure that's a troll strangling a puppy. |

Meanwhile, this article from 2009 says Cracker Jack was being sold in bags already back then, so the affront to American innovation and baseball is older than the Gizmodo article, which is an affront to journalism. (Even more of an affront? Gizmodo's writer probably just cut-n-pasted the news from sites like Today and CBS News. Hip'n'trendy writing notwithstanding, Gizmodo is just a news aggregator like HuffPo.)

As for "American" innovation, "Cracker Jack" was developed by a German who came to America, bought out his partner and brought his brother over from Germany. The brand's roots as a snack first presented at the World's Fair in 1896 is likely a lie. the inventor of the packaging lived in Ontario -- not a part of America! -- at the time of his death.

Changing a box, a prize, an ad, a logo is not an insult to America, or baseball. But pretending that 3-year-old news copied from another website is original thought is an insult to me.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)