Is it torture or not? It’s so borderline... It’s like minimal, minimal, minimal torture.”

-- Donald Trump, vowing to bring back waterboarding.

Saturday, February 20, 2016

Thursday, February 18, 2016

Throwback Thursday: Somehow I managed to allow pizza toppings to be given credit for THE SPACE PROGRAM.

The topic of pizza, and specifically what is a pizza, or when is a pizza really a pizza, is suddenly all over the news this week -- from Antonin Scalia's death making people recall that he once proclaimed deep dish pizza to not be real pizza to yesterday's Dinosaur Comics:

Anyway, like most things, I've thought of this stuff first, and the rest of the world is only just now getting around to catching up to where my head was at years ago. 7 years ago, more or less, when I posted The Best Pizza Topping. I've reprinted it below; as usual with posts like these, my comments as I re-read it are in red.

_______________________________________

Yesterday, I had a lot of time to think. And this topic is one of the things I thought about. Specifically, here's what happened: I was driving home from Milwaukee, about a 1 1/2 hour drive, and I put on the song "This Guy's In Love With You" performed by Herb Alpert & His Tijuana Brass. You know the song, right?

And as I listened to that song, this thought suddenly occurred to me:

When does a thing stop being that thing and start being something else?

Which doesn't immediately, I know, make sense, but it will, if you bear with me as I do a little thought experiment.

Picture a ray. You remember "rays" from math class in high school, right? A line extending from a point in space off into infinity, represented by an arrow with a dot at one end.

Yeah, the middle one. Picture that ray, and assume that point "C" represents "pizza" the way "pizza" originally was intended to be represented, like, say, this:

Maybe that's not your idea of a pizza. Maybe your idea of a pizza is something thinner crusted or square or with anchovies or whatever, but that's not the point. Or it is the point but I'm not yet at the point where I'm ready to make my point, so whatever your idea of a pizza is, of the quintessential pizza, get that picture in your mind, and picture your own Quintessential Pizza as the point at which the ray begins.

Got that? Now, picture, in your mind, making more and more changes to the Quintessential Pizza, each change moving you a little further along that ray, each change not a big deal, in and of itself, not so far removed from what came before, but each a change nonetheless. As that happens, as you keep making little changes here and there to your Q.P., this mathematically- and scientifically-accurate diagram gives an idea what happens:

As you can see from that Scientific chart, at some point, you, the Q.P. creator, have moved so far away from your starting point that we, as human beings/scientific observers, have to ask, in the interest of philosophical, intellectual inquiry, this question:

Is what you've got really a pizza anymore?

Which begs this question:

What is the essence of a pizza?

Which begs this question:

What is the essence of ANYTHING?

Which is how you can get from Herb Alpert to questioning the very foundations of human existence via pepperoni.

But this is a serious question, albeit a serious question I am choosing to answer via the method of "pizza-as-demonstrative-example." (I was about to say "Pizza-as-allegory," because that sounded good, but the pizza isn't really allegorical in this article, it's demonstrative.)

Which begs this question:

Which sounds better, "Quintessential Pizza" or "Allegorical Pizza?"

I think the answer is "Allegorical Pizza." But anyway, the pizza in this article is not allegorical, it is demonstrative of the question of when a thing stops being that thing, a question that actually was on my mind because I read the "novella" Disquiet on Saturday. Disquiet, by Julia Leigh, is a very, very good story. After I read it, though, I questioned whether it is a novel or novella or a long short story, and then I wondered whether that matters.

I think the answer is "Allegorical Pizza." But anyway, the pizza in this article is not allegorical, it is demonstrative of the question of when a thing stops being that thing, a question that actually was on my mind because I read the "novella" Disquiet on Saturday. Disquiet, by Julia Leigh, is a very, very good story. After I read it, though, I questioned whether it is a novel or novella or a long short story, and then I wondered whether that matters.I decided that it is a very long short story, and that yes, it does matter.

Here's how I decided it's a very long short story: the transformations that the characters go through are ambiguous and not clearly explained, and much of the plot occurs offscreen or is left untold. That's the criteria I apply to a short story, as opposed to a novel. A novel is not only longer, but has more development, more wrap-up, more explanation.

In a short story, a character might (as one of mine did, once) get in her car and try to drive away from her house with her young daughter, only to rethink her actions as a thunderstorm starts to set in, and go back. And the reader might (as my readers were) be left to wonder or fill in the blanks as to why the woman is leaving, why the thunderstorm makes her change her mind. The short story shows an episode in the woman's life with some explanation but with little change in her and with little beyond that episode explicated.

If that story were a novel, though, we would expect more detail, more plot, more description, more backstory, more of everything. The short story is a snapshot; the novel is a photo album.

That's not to say one is better than the other; it's to say that each label carries with it a set of expectations and rules that guide the writer, and the reader, and determine how they should interact with each other through the medium being used. A short story cannot be said to be better or worse than a novel any more than a sculpture could be said to be better or worse than a painting.

The problem, if there is one, arises when we use the wrong terminology to describe something. If I told you to come to my house to see a sculpture, and showed you "Red Yellow Blue,"

you might be mystified. That's a painting, you might say, and while you might like "Red Yellow Blue," you may find yourself befuddled because you were expecting a three dimensional sculpture only to be presented with a two dimensional painting.

Or maybe you think you did see a sculpture, because "Red Yellow Blue" is three canvases separated from each other so that it is more than a two-dimensional splattering of paint on a canvas, it takes into account the space between the canvases and can be rearranged and in that way fully inhabits or more fully inhabits a three-dimensional world than a "painting," but is it a sculpture? When I say sculpture, do you think of "Red, Yellow, Blue," or do you think of this:

And if you do think of that, why didn't you think of this

when I said "sculpture?" Aren't they both sculptures? Of course they are: but one is more sculpture-y than the other. One is more a quintessential sculpture.

Which is my point again, here. At some point, a sculpture stops being a sculpture. As it gets bigger, and more made of metal, and more standing-in-a-harbor-in-New York, it stops being a "sculpture" and starts being a "statue" or "monument." And as it gets flatter and more primary-color-ish and on canvas, it stops being a "sculpture" and starts being a painting.

So as Disquiet failed to tie up all of its storylines, it stopped being a novel and became more of a short story. Which was not a bad thing. It wasn't what I expected, because I was told it's a novel, and so I expected more wrap up, but given the nature of the story and the general feel of the story, being left hanging somewhat at the end despite expecting more resolution wasn't a bad thing itself, either -- it made the story more of a meta-story, instilling in me one last time the exact feeling (of disquiet) that the author was going for.

So maybe messing with one's expectations can work, in some instances. But in pizza? That's where we began, after all, to consider whether a thing can ever stop being a thing, and as this discussion is important, it will help to keep it rooted in the things of reality: Herb Alpert and pizza.

So when is a pizza no longer a pizza? Is a breakfast pizza a pizza? I had a sample of breakfast pizza at the store two weeks ago -- miraculously, given that pizza samples are amazingly rare in the real world, and I had to wonder is this pizza? It was round -- like a pizza, except that sometimes when I make pizza at home I run out of pans and have to resort to making some of them square or rectangle. It had a pizza crust on it, which is like a pizza. But it had eggs and cheese, and while pizzas have cheese they don't have breakfast-y kind of cheese on them, they have pizza-y kinds of cheese on them: mozzarella, which I think is chosen for the way it can hold everything on the pizza while not having much actual flavor, which is why I usually substitute in some other kind of cheese on my homemade pizzas: I like the stronger flavor.

The breakfast pizza was toasted in a toaster oven, but aren't pizzas supposed to be cooked in pizza ovens? I sometimes grill mine, too, making them using the broiler setting.

All of which leads to much confusion: was this breakfast pizza sample a pizza at all? And if it was a pizza, why is it a pizza?

What about the "mashed potato pizza" that I sometimes make using an idea I stole from a pizzeria -- making a pizza crust and then putting mashed potatoes into it and then topping it with pizza toppings and baking it? Is that a pizza?

And if it is, what about the "fruit pizza" my mother-in-law makes -- that's a sugar cookie with fruit and frosting on it. Is that a pizza?

If that's a pizza, then isn't everything a pizza? If all that's required of a pizza is that it be round, more or less, and be called a pizza, then isn't this:

a pizza if I call it a pizza?

I come down on both sides of that issue. I understand the allure of saying that things have to be what we call them, that everything has to have a category, that a pizza must have some definable quality or qualities that makes it a pizza and that if something doesn't have all or most or enough of those qualities, then it's not a pizza, because then everything makes more sense and expectations are not dashed and we all know what we mean when we invite each other over for pizza -- nobody will be invited over for pizza and be served eggs on a crust, or fruit on a cookie.

But on the other hand, I see, too, the side that says anything can be a pizza if we want it to be, for two reasons.

First, the practical: I want to be aligned with the anything can be a pizza crowd because my pick for The Best Pizza Topping is mashed potatoes. Ever since coming across the potato pizza as an appetizer in that restaurant, I've loved the potato pizza. Done right, it is (as the pigeon might say of the hot dog) a taste sensation. It combines the mushy-but-crisp-edged creaminess of a twice-baked potato with the gluey cheese and savory tomato sauce and spicy sausage and fruity pineapple and zing of the onions that I like on my non-potato-pizzas, and does so in a way that creates a new feeling, a new thing that is both pizza and not pizza at the same time.

There is the impractical, esoteric reason why I see the appeal of the anything can be a pizza argument: the ability to grow and change and become something new. If we rigidly define life's categories, if we say a statue is a statue, and a pizza is a pizza, and things that aren't quite statues or pizzas aren't statues or pizzas at all, then we are limiting ourselves and our thoughts. We'll be saying to our imaginations: no, you can't put that on a pizza, or no, you can't sculpt that or no, Herb Alpert, you can't have the Tijuana Brass play with you (it'd been a while since I'd mentioned Herb) and we'll say that because pizzas don't have that, whatever that is, on them -- so pizzas will never have that on them, and limiting ourselves like that raises the prospect that we'll stop innovating at all.

After all, it's easier to take tiny steps than giant leaps. It's easier to decide to move a city away than a continent away. It's easier to move from painting to sculpting if a painting can kind of be a sculpture. It's easier to try to mix something into your pizza than to create an entirely new dish... but doing all those little steps leads you into a direction that you might not have tried, had you had to do it whole hog right off the bat. How tough was it, do you suppose, for Columbus to get on his ship and sail towards the edge of the world? Pretty tough, I imagine. What if, instead, Columbus had known of five, six, seven island chains all stringing off into the west, and had decided he was just going to follow them and see if there was an eighth and instead of finding the Eighth Islands, he found America?

What if the space program, instead of trying first to get to the moon, had set off for the nearest star outside our solar system, Proxima Centauri? That's only 4.2 light years away. Voyager, our fastest spaceship, moves at 17.4 km/second. At that rate, it would have reached Proxima Centauri in 7 million years. Why would we have even tried to go into space if we wouldn't see results for 7 million years?

What if the space program, instead of trying first to get to the moon, had set off for the nearest star outside our solar system, Proxima Centauri? That's only 4.2 light years away. Voyager, our fastest spaceship, moves at 17.4 km/second. At that rate, it would have reached Proxima Centauri in 7 million years. Why would we have even tried to go into space if we wouldn't see results for 7 million years?Tiny steps, incremental changes, minor modifications, shifting standards, can lead to big things. Not pigeonholing things into one category lets people experiment with tiny steps and incremental changes. And, not pigeonholing things into one category allows the mind to wander. It allows people to expand their mental horizons, to picture more than one thing when just one word is used, to play with the shifting sands of our imagination and in doing so, create something new, something wondrous, something that challenges our expectations and makes us think, at the end of our novel, or as we bite into a pizza, or look at a painting: "Hmm. Well, that was interesting. That wasn't what I expected at all."

In the end, that's one of the best things about Mashed Potatoes being The Best Pizza Topping: allowing mashed potatoes to be pizza opens the door for a world where one can move from pondering Herb Alpert to questioning the very basis of reality -- and that kind of world is the kind of world I want to live in, the kind of a world where a thing never stops being that thing but can be that thing and something else, entirely, all at once.

_____________________________________________________________________

When I first wrote that, I had never heard of the Ship of Theseus philosophical conundrum, and had not heard of the Platonic ideal of things. The Ship of Theseus argument actually fascinates me the most -- and I'd touched on it that essay, well before I ever learned that such a question had long been pondered by the brightest minds of previous civilizations.

I guess what I'm trying to say is: Since pizza got the space program started, I am obviously 2016's Aristotle.

Wednesday, February 17, 2016

This is how I like to think this went down

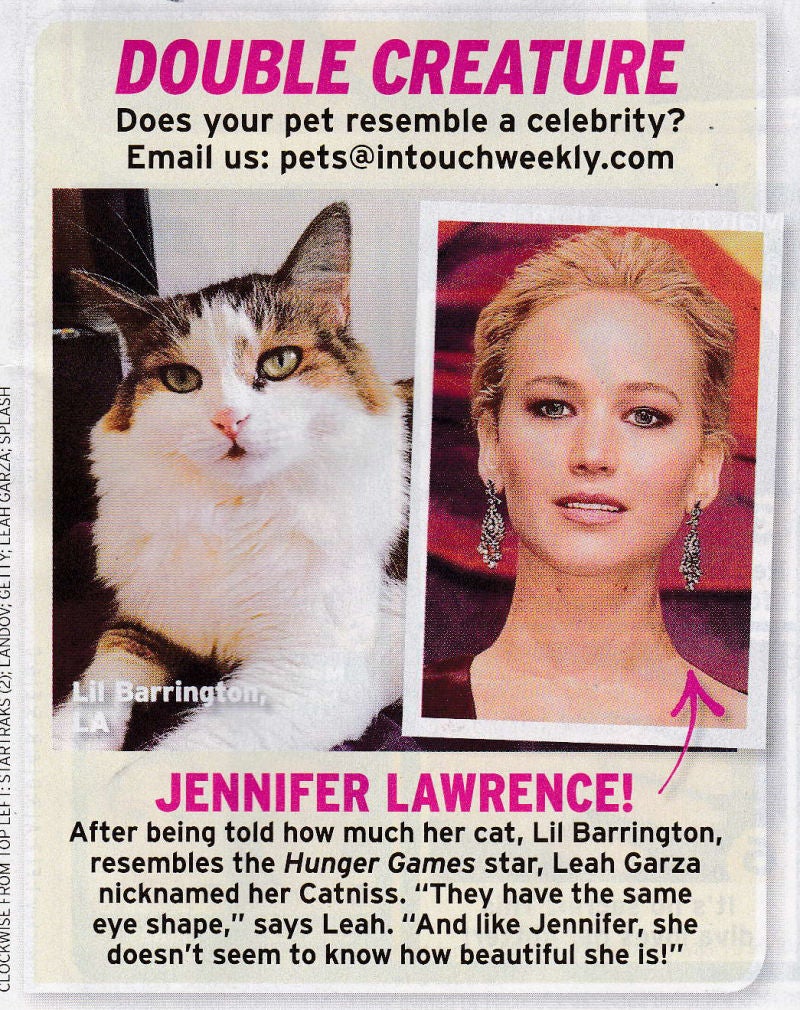

Author of The Hunger Games *thinks to herself* “I really want to name my main character after my best friend but I can’t let everyone know how desperately lonely I am... I know, I’ll change the C to a K and nobody will be the wiser.” *goes off to see if new issue of O magazine has arrived.*

Cat owner Leah Garza *thinks to herself* I really want to name my best friend after the only thing that’s ever brought meaning to my life but I can’t let everyone know how desperately lonely I am... I know, I’ll change the K to a C and nobody will be the wiser.” *decides to drink a pumpkin spice latte out of season because she is her own woman*

*****

"Hey your pet really looks like [famous person]"-- Nobody, ever.

_________________________

Nine Inch Nails' songs include Hurt, The Perfect Drug, Head Like A Hole, and other greats! Now your toddler can celebrate them!

The Nine Inch Nails toddler shirt: for when you've become a parent but still want to be a goth kind of.

Tuesday, February 16, 2016

I'm just saying, maybe you follow me on Twitter, maybe I don't have to keep reposting my tweets here...

Scalia's body was found with a pillow over his face: https://t.co/UdWJ8bCcBg Officials suspect a cover up.— BrianePagel (@BrianePagel) February 16, 2016

Funny stuff, right?

There is some pretty weird stuff going on with his death, though, including now just how the body was found, but the fact that in Texas you can be declared dead by a judge who hasn't even seen your body. Texas: Come for the gun nuts, stay for the insurance fraud. (Copyright 2016, Texas Tourism & Shootin' Bureau.)

Here's a post I wrote way back when about the time in 1994 that I got to meet Justice Scalia:

Everyone has one year in their life that has a greater impact on them than any other year. Mine was 1994. Once a week, I'll recap that year. This is part 17; click here for a table of contents.

As memoirs go, this isn't much of one. It's as much about the process of trying to remember as it is about remembering, and as much about what I think about things now based on what I did then as it is what about what I did then.

Which maybe is the point.

But memoirs are supposed to have high points and great events -- like Dr Iannis in Corelli's Mandolin, who wanted to write history but then realized, no, he wanted to live through history -- or they're supposed to have quirky bits in them, like people that go live in a chicken coop for a year to see what that's like. They're not supposed to be (I thought) ruminations on things ranging from license plates to ice cream, and they're probably not supposed to drop storylines and thoughts like uncooked pasta and never come back to them, kicking those things under the oven to leave them there until they're found someday upon spring cleaning (which sometimes happens at times other than the spring.)

I don't think this part of the memoir is quirky, at all. The part coming up, the part where I lived in Morocco, is probably quirky, at least at times, but the Washington D.C. part, the part I've been focused on for sixteen installments so far, doesn't seem quirky or monumental, and it is chock-full of Dropped Pasta -- like my attempts to quit smoking, and my then-sometimes-girlfriend, and even Rip, the guy who lived in my room with me for months and months and months, and about whom you've heard little. And like Carlos, another good friend of mine who may have been from Paraguay or may have been from Uruguay but who also was from a college in Pennsylvania -- maybe Slippery Rock -- and whose parents, I recall, may have been bigwigs in whatever 'Guay he hailed from -- and who was such a good friend of mine that he not only shows up in some pictures from that time but also he rode the train back with me from D.C. to Pennsylvania, where he said goodbye and promised to stay in touch (he did, I didn't) and promised that we'd get together again in the future (we didn't.)

Those people have put in cameos in this memoir, and if it seems they should have had a larger role, that they should have been pictured as many times in my photos from that trip as, say, Hsing Hsing and Ling Ling (the pandas that lived at the National Zoo at the time, and who were underwhelming when I saw them... well, not underwhelming, but they didn't live up to the hype. They were... well, they were just-whelming), if it seems that someone who was my roommate for months on end should figure more prominently in a memoir of that time than a not-remembered diamond, then all I can say is that my memoirs, like my memories, and like my life, don't tend to follow suit. Because I've got one picture of Carlos, and two of the pandas. In the end, from a perspective fifteen years later, looking down the telescope backwards as it were, Carlos and Rip and Frank and Dave and the son of the Shah of Iran and even Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia played cameo roles in my life. They seemed, at the time, to loom large. They seemed, at the time, as though they were significant, but they weren't. They were, in terms of their impact on my life, less important than the first few characters you meet in every episode of Law & Order.

You know what I'm talking about. In every episode of Law & Order, some random character comes along a city street at night, or jogs through a park, or checks her purse for change by a parking meter, or babbles excitedly to his fiance outside of the Statue of Liberty. Then, Random Person spots a body, or bloody stump, or shoe, or something, and they virtually fade out of the episode -- maybe talking to Lenny for a minute or two more before exiting the episode, never to be seen again.

Frank, Rip, Dave, the Son of the Shah of Iran, quitting smoking, Hsing Hsing: these people simply introduced, maybe, storylines to come later, as did Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia.

I can't be blamed, I think, for not wanting to downgrade meeting a Supreme Court Justice to a mere cameo in my life. I didn't, in fact, downgrade him to that position until just today, when I decided to write about meeting him because memoirs are supposed to have monumental figures, and meeting a Supreme Court Justice is the closest I've come to meeting someone who is monumental.

Only he wasn't, and it wasn't. In terms of the impact on my life, meeting a Supreme Court Justice was not, ultimately, as significant as any hundred other things I've done. In terms of my memory of meeting him, I have a pretty good recollection of spending time with him. But I have a better recollection of, among other things, an afternoon I spent jogging, including going past the fire department in Hartland, Wisconsin, while listening to Paul Simon's "Graceland" on cassette tape; of the drug store in Pewaukee near the lake where I'd sometimes ride my bike to in the summer, when I was 13 or 14 or 15, buying a snack and some comic books and then riding home, of playing frisbee golf in the forests of northern California with my family and my sister on vacation. I remember all of those things about as well as I remember meeting Justice Scalia, so how monumental can he be?

Anyway, when you meet famous people in real life, they almost always disappoint, and people who are famous for governing are maybe more disappointing that people famous for doing things that aren't so important. I mentioned meeting Senator Bob Packwood, and one would expect him to disappoint, maybe, as a disgraced Senator on his way out. In that, he actually didn't let me down: leaning tiredly in the elevator, he appeared to be, in hindsight, exactly what I would have wanted him to be: a reduced figure, a man of some importance at one point, elevated to prominence only by the fact that he was about to be removed from prominence (as so many of our politicans' career arcs go).

I met other famous-for-governing people before and after Justice Scalia. I met Senator Herb Kohl, a Senator who is beloved in Wisconsin for being "Nobody's Senator But Yours" or some slogan like that. Herb Kohl was a self-made millionaire, or maybe billionaire, who started up "Kohl's Food Stores," a chain of groceries in Wisconsin that maybe doesn't exist anymore. He then started Kohl's Department Stores, which still exist around here, and which I still shop at sometimes, mostly when I accompany Sweetie to pick out a new outfit for her or the Babies! or the kids, or, at Christmas, when we always seem to go there to get someone a sweater as a gift. Along the way, or after that, Herb Kohl also bought the Milwaukee Bucks (which he still owns) and eventually paid some or all of the cost for the "Kohl Center" where the Wisconsin Badgers play basketball. As part of his life, he became a Senator, too, apparently on the grounds that as a million/billionaire, he could not be bought by special interests and also on the grounds that people in Wisconsin really like him.

I met other famous-for-governing people before and after Justice Scalia. I met Senator Herb Kohl, a Senator who is beloved in Wisconsin for being "Nobody's Senator But Yours" or some slogan like that. Herb Kohl was a self-made millionaire, or maybe billionaire, who started up "Kohl's Food Stores," a chain of groceries in Wisconsin that maybe doesn't exist anymore. He then started Kohl's Department Stores, which still exist around here, and which I still shop at sometimes, mostly when I accompany Sweetie to pick out a new outfit for her or the Babies! or the kids, or, at Christmas, when we always seem to go there to get someone a sweater as a gift. Along the way, or after that, Herb Kohl also bought the Milwaukee Bucks (which he still owns) and eventually paid some or all of the cost for the "Kohl Center" where the Wisconsin Badgers play basketball. As part of his life, he became a Senator, too, apparently on the grounds that as a million/billionaire, he could not be bought by special interests and also on the grounds that people in Wisconsin really like him.I was able to arrange a meeting with Senator Kohl in Washington simply by going to his office to meet him. I went to the office, located in one of the office buildings off the Capitol, and found a receptionist and explained who I was and asked if I could meet the Senator. I'd tried this same thing with Russ Feingold, our other senator at the time (and still.) Russ hadn't been in when I stopped by to meet him, and so I wouldn't meet him in Washington, at all.

(I would, coincidentally, almost meet Russ years and years later when I moved to Middleton, Wisconsin, with Sweetie and then joined Sweetie's health club, a health club that Russ Feingold also belongs to. I see him there, sometimes, working out. He doesn't look like a senator when he goes to work out, but it's hard, I suppose, to look senatorial when jogging or biking.)

Herb Kohl was in, and the receptionist got him, after only a short wait. He came out, a short, hunched-over kind of guy with a bald-and-very-red head and very white hair and a smile on his face. He shook my hand, he asked me what I was doing in Washington, he asked me what college I attended, and made a few more bits of small talk, and that was it. He thanked me and went back to work, doing whatever it is Senators do all day in their offices.

I should know what Senators do all day in their offices, as a political science major, but I don't, because they don't teach you that kind of thing in political science, or in college, period. They teach you a bunch of other stuff, but nothing nuts-and-bolts about what it is that Senators do all day or how to be a Senator or whether there's a particular kind of handshake you'll want to use when meeting with college students who pop in to interrupting your Senatoring. Everything I know about what Senators do all day I know because I talked to Rip, who worked in a Senator's office, and I know because I read Parliament of Whores by P.J. O'Rourke, a book that really should be required reading for anyone who lives in America.

What Senators do all day is not immediately apparent from what we see Senators do. What we see them do is talk on TV and make speeches (usually with some sort of prop behind them) and we see them watch the State of the Union and, in TV shows, they sit behind desks and get quizzed by reporters or cops. But there's a lot more that goes into Senatoring, I gather, than that, and most of that "lot more" is either boring, fake, or done by interns and staffers.

Rip, as an intern/staffer, had a variety of jobs that he would tell me about from time-to-time, most of them looking into constituent concerns, which mostly meant "reading mail." Rip got to read the mail for the Senator, and respond to some of it, I think. Rip also talked about people coming in to meet with the Senator he worked for, and talked about staffers researching bills and staffers being lobbied, and the Senator being lobbied.

That, together with P.J. O'Rourke's description of how a representative spent his day -- mostly rushing to and from votes with a little card tucked into his pocket telling him how he stood on a given issue -- and with my own observations around Washington form the basis for what I know about what Senators do, and beyond that, I've never been very curious, other than to think, from time to time, that they appear to have a relatively stress-free job. It seems as though a political science major interning in Washington D.C. should both have wanted to learn more about the process of governing, and have actually learned more about the process of governing, but I didn't really care about that at the time and was more interested in seeing the sights in Washington and more interested in trying to meet famous people who might help me on my rise to fame. Which of these people, I occasionally wondered as I met them or tried to meet them, might be the person in the photo that news shows put up in the future to show when I began my own rise to prominence and fame. There's always such a photo, such a moment, for politicians, at least nowadays, and at least since Clinton met Kennedy.

The answer, I know now, is none of them. There were no photos with Herb Kohl, and fifteen years later he's not shown himself to be the kind of prominent politician that would inspire such comparisons even if I had myself become a prominent person instead of a quiet lawyer in Madison. It's unlikely that if I'd become president by now (I'm eligible, at least) that Katie Couric would have shown a picture of me meeting Herb Kohl to highlight the early beginnings of my career, and not just because there were no such pictures, but also because it was not a particularly inspiring moment. It was more of a pleasant interlude with a guy who seemed as though he'd be more at home sitting on a front porch genially telling kids it was okay to play on his lawn but would they mind the geraniums?

I had higher hopes for my meeting with Justice Scalia. I'd gotten the opportunity to meet Justice Scalia as part of my letter-writing campaign, writing to famous people and groups and asking how I could meet them or join them. I'd written to Justice Scalia and explained that I was here on an internship, that I admired his legal writing and philosophy, that I'd written a term paper on an opinion he'd authored in one of my classes that had dealt in some way with the judiciary, and could I meet him?

Then I'd forgotten about it amidst all the jogging and trying-to-quit smoking and wondering what it was I was supposed to be doing all day at my internship and my general-bumming-around-Washington D.C., forgotten all about it until I got a letter from Justice Scalia's office telling me that he'd be happy to meet with me, and I should call to make an appointment.

So I did; I called right that day, using the old black rotary phone with the phenomenally long cord that hung on the wall just down the hall from our dorm room -- the community phone to be used by our whole section of the dorms, a phone that had to be used amidst everyone else who was using the dorms, so that any phone call was made in a tile-and-cement hallway reminiscent not just of dormitories but also of middle schools and state Health & Human Service Departments. Phone calls to girlfriends to talk with them because one felt like he had to call his girlfriend even if he didn't really feel like calling to talk with his girlfriend, phone calls to family members to say "Hello" and hint around that if people wanted to send, say $100, it would be appreciated, and phone calls to Supreme Court Justice's offices, all were done amist people smoking and showering and walking around in towels and, for one group of guys, playing a semester-long, neverending game of "Axis and Allies," a wargame that I, too, loved, and which I secretly always wanted to be invited to play but never was. I even once said to one of the guys "Maybe I should jump in and play a game with you guys," only to get shot down -- he said "We're in the middle of a game and I don't know when it'll end."

He didn't say "But we'll get you on the next one" and I noticed that and never asked again, but I did, from time-to-time, listen in on their games, on the rolling dice and talk about who was invading who and who would regret strategic moves. I didn't want to be friends with those guys, I didn't want to sit around talking to them or anything. I just wanted to play Axis & Allies, because I loved that game. I don't even know how those guys, and those guys only, got to be the Axis & Allies guys on the floor; I don't think they knew each other when the semester started. I think they just ended up playing a game of Axis & Allies and became friends as a result of that, forming a clique that way and excluding others. Maybe if I'd been more outgoing that first night, I sometimes thought, I'd have jumped into that game of Axis & Allies instead of hanging out with Rip and Carlos and sometimes Mike, the Bald Guy who smoked a lot -- who smoked so much that when he tried to quit, he used the patch, and would smoke with the patch on, something he said gave him "weird dreams." I might have hung out with the Axis guys instead of hanging out with the guy who taught me how to play power chords on my guitar, a guy whose name I can no longer remember but whose legacy lives on in my ability to play So Far Away, Hitchin' A Ride, and Gimme One Reason on my acoustic guitar.

In that respect, I got more out of Guy Whose Name I Can No Longer Remember than I did out of meeting Justice Scalia. I called Justice Scalia's office the day I got his letter, calling from the dorm phone and setting up an appointment.

"Hello?" came the voice on the other end, and, as instructed by the letter, I asked for the justice's appointment secretary. Mrs. Toughill got on and I said who I was and why I was calling.

"Oh, yes," she said, "I know your name."

"I'd like to set up an appointment with the Justice," I said.

"When would be convenient for you?" Mrs. Toughill asked me.

For me? I said: "No, no, I'll meet whenever it's convenient for the justice," I said.

She then reviewed his schedule, noting which days the Court had oral argument and that those times were out (as he'd be in Court listening to the arguments) and we finally settled on an appointment.

When that day came, I dressed up in the nicer of the two dress shirts I had, and put on the nicer of my two sportcoats-- at the time I had only two coats, a dark gray and a lighter gray, and the lighter gray seemed the more serious and monumental of the two, and I put on a tie (I had about four ties) and I rode the Metro down to the Capitol area, where the Supreme Court building was located not far from the Capitol itself, and a little ways away from the White House.

The White House doesn't actually sit directly next to the rest of the government. It's on the National Mall, but it's off to the side. At one end of the Mall is the Lincoln Memorial, and then in the center is the Washington Monument, and then at the other end is the Capitol. Midway through that, and off to the left if you were standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial looking down the Mall, is the White House.

The Supreme Court building is up near the Capitol and Union Station, near where I'd first arrived in Washington. I got to the building early and made my way up the stairs. I walked up the stairs with interest: in getting the day off to go meet with Justice Scalia (a meeting Frank had wholeheartedly endorsed, I suspect partly on the basis that it was important that interns get to do those things and partly on the basis that I wasn't very much help around the office, anyway), in asking for that day off, Frank had told me more Washington lore, in this case a story that the architect of the Supreme Court building had deliberately designed the steps in such a way as to make them, for most people, slightly too long to be taken in one regular step, but slightly too short to be taken in two regular steps, the result being that when you walk up the steps to the Supreme Court, you must alter your gait, and do so very deliberately, taking smaller and shorter steps. Frank told me to look for that, and said that the architect had done that so that people approaching the Court would do so solemnly and deliberately and know that they were approaching a building in which important happenings took place.

Frank may have been making up that story -- I never verified it -- but he was right about approaching the Supreme Court building; it was tough to just walk up the stairs, and I couldn't do it. No other stairs in D.C. were quite like that. There were lots and lots of stairs, most of them small and narrow and steep, the way stairs were made back in the days before "trial lawyers" got a bad name, but no other stairs in D.C. made one walk in a weird, step-and-a-half gait.

The only other stairs I've ever seen anywhere like that, in the entire world, or at least in the portion of the entire world I've visited, are my front walk. The stairs to my front door in the house Sweetie and I bought seven years ago are, philosophically, identical to the stairs up to the Supreme Court building: they are too long to take in one step, too short to take in two regular steps. So each day, when I return home from work, I walk up to my front door in the same exact manner that I approached, fifteen years ago, the Supreme Court building: slowly, deliberately, and with a slightly odd hitch to accommodate unusually-lengthed steps.

Weird.

I got inside and didn't spend much time walking around before I went in to meet with Justice Scalia. He was, like almost every other famous person I've met, short. He barely came up to my shoulders. I know that I'm kind of tall for a person, at 6'1", but that doesn't account for the fact that almost every famous person I've met has been not just shorter than me, but shorter than average.

Justice Scalia's office barely registers in my mind now, and I hesitate to describe it because I'm not sure how much I remember and how much I've filled in over time. In my mind, when I picture "Justice Scalia's office," I think of a wide, broad, long, old, solid desk with brown edges and a black top, with the chair backed up to a window that had wooden slats on it, looking out onto a garden of sorts. I think of walls lined with deep bookshelves and books upon books upon books. I think of a coatrack in the corner, wooden, bare because it was spring and a warm day.

But that's exactly what a Supreme Court justice's office should look like, and so I don't trust that it actually looked like that. If you want to picture it that way, feel free to do so; it can't hurt.

I introduced myself and thanked him for meeting me, and he was nice about it.

"So," he said. "Do you have any questions for me?" It had not occurred to me until that point that I should have questions for him, that as a political science intern student meeting a Supreme Court justice, I should have things that I'd like to ask him. I had nothing.

So I asked him this: "Is it as great as it looks, being a Supreme Court Justice?"

I have never pretended to be a philosophical person.

He said it mostly was; he said that it was a very good job, and added the obligatory reference to it being a lot of hard work and a lot of effort, about which, I think, now, fifteen years later, that it's not hard work at all, being a lawyer, and it's probably not hard work at all, being a Supreme Court justice, not hard work in the sense that being a construction worker or soldier is hard. It may be time-consuming, but it's not hard and it's not a lot of effort.

But I didn't say that, then. I asked him, instead: "What do you spend your time doing, all day?" And he explained to me, about listening to oral arguments, and researching for opinions, and writing opinions, and re-writing opinions, and debates in conference about how they were going to vote. It sounded thrilling to me then, but it sounds to me now like exactly what I do all day (absent the blogging, of course.) And I know that what I do, while interesting to me, is not thrilling or interesting to most people (including a kid that I had follow me around for a day, once. He wanted to see what it was like to be a lawyer, as part of his high school project, and arranged through a client of mine to "shadow" me, spending a day sitting in on hearings and negotiations and the like. Six months later, he sent me a note thanking me and letting me know that he would not be going on to be a lawyer.)

I asked Justice Scalia, and this is the part I remember most clearly about that meeting, whether the upcoming change in Supreme Court justices was a big deal for him. The Court was at the time, just a few months shy of Justice Breyer taking his seat, and I asked whether that made a big impact in his job and his life.

"Not really," he said, and I remember that because I remember thinking how could that be true but he then went on and said "You know what makes a big deal? We've got a bailiff retiring whose been here a long time. That makes a big change in your daily routine, losing a longtime staffer like that."

We talked a little more, and I got my picture taken by his secretary. I remember that, too. She came in when he buzzed her and I got out my old 110-film camera and handed it to her. We then stood back and waited while she tried to take the picture, only to have her unable to figure it out, so I had to show her again how to use it, and Justice Scalia made a joke about that. He then shook my hand, wished me luck, and sent me on my way.

I thought, in going to meet with him, that it would be a pivotal event in my life. I was, after all, majoring in political science. I was in Washington, D.C., with a career arc ahead of me that at that point included maybe the Foreign Service, maybe politics, but certainly something big, something important, something monumental. I was, I figured, going to live history, and someday, I guessed, I'd look back on this meeting as the starting point, or a starting point, or at least a significant point along the way to my rise to fame and fortune and power and the stunning heights that I was expected, and which I fully did expect, to reach.

Now, fifteen years later, I've got that picture hanging on my wall, in a frame that also includes other things I did that year. That frame hangs on my own office wall, amidst my diplomas and certificates of admission to the Bar and articles I've had published, but also amidst a small joke sign my dad gave me that says I can't be fired, Slaves have to be sold and amidst pictures of the kids, and right next to a picture I took of a decorative lion's head on the Wisconsin Capitol, a building I walk by every single day of my life.

It's just one tiny picture among the other pictures on my wall, and among the other pictures on other walls. It's dwarfed by the watercolor I drew of some flowers that used to grow in a pot on our patio. It sits across from a photo collage of the neon signs in Las Vegas from the family vacation we went on five years ago, and it's smaller than the picture of me standing side by side next to an Elvis impersonator outside a casino. By sheer numbers alone, the Me & Scalia photo is losing the battle: there are 35 photos that have one or more of the kids in them. There are 8 photos that have Sweetie in them. There are 7 photos of things I just thought were interesting and so I took a picture of them.

And there is one each of photos showing Oldest practicing karate, me wearing a clown nose, Mr Bunches sleeping on a bench, the World Trade Center, a little league team I coached, me standing in my father-in-law's living room in Oakland, and me standing next to a Supreme Court justice.

Me and Scalia got lost in the shuffle.

Which maybe is the point.

Monday, February 15, 2016

Things I learned about trainyards today.

While drawing the Railroad ABCs for Mr Bunches, mentioned that trainyards have "pipes, oil, tracks, and also chocolate."

This has been "Things I learned about trainyards today."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)