It really says something about how great the first 90% of The Gone Away World is that the finale is the least memorable part of it -- especially because the finale is, itself, a phenomenal piece of writing that caps the story perfectly.

I've read The Gone Away World before, but I wanted to go back and read it again, so this time I did it on audiobook. What I was surprised about was that I remembered, almost verbatim, that first 9/10 of the story, but could only vaguely think of what happened after the big reveal in the story, the swiping aside of a curtain that moves the book from great to phenomenal. I think that's because, like I said, while the ending is great, what comes before it is so perfect as to obscure the closing chapters. It's like sitting on a sunny beach on a bright, calm day with a blue sky having just enough white fluffy clouds in it overhead, and in your hand is an icy drink and the sun is warm on your face, and off in the distance just barely audible a radio is playing a song you love from when you were 13, and your beautiful wife is lying next to you while your kids play in the breakers, and then someone puts Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel there, too. (The ending is the Sistine Chapel.) I can only think of two books that have made me think this: this one, and The Passage. In each the beginning part of the story is so overwhemlingly good that nothing could compare, it has to go down or at least not keep going up.

The Gone Away World is told from the perspective a nameless narrator who hangs on the edges of the life of his best friend, Gonzo Lubitch. He tags along with Gonzo, an athletic daring handsome guy who attracts all the attention and never wants for excitement, through growing up, learning martial arts, going to college, getting briefly abducted by the government and suspected of being a terrorist, getting forced into a shadowy branch of the military, ending up in a war on a small island that results in "The Go Away War," in which all the major countries use a new kind of bomb that takes away the information from matter, resulting in things just... disappearing. This has the unforeseen effect of leaving the world swarming with matter waiting to be formed into something, and when that matter comes close enough to a human mind, it goes through 'reification,' becoming what that person is thinking about. Because this results in a nightmarish sort of existence, a pipeline is built around the world to spray a chemical that neutralizes the free matter -- and then the pipeline is attacked, and Gonzo's crew has to fix it.

That all sounds complicated enough, but the book is so much more than that. Nick Harkaway crams the book full of characters and details and ideas and philosophies, and what's most amazing about it is that not a single one of them is wasted. Every single sidetrip down some minor character's past, every single conversation in a bar, every throwaway reference to bees or Tupperware -- both of which play major roles in the book -- ends up being absolutely integral to the book. It's amazing and awe-inspiring, even more so the second time around when I could really focus on the details. If you've ever seen a cartoon where someone like Bugs Bunny throws a bunch of bricks in the air and then they come down and form a perfect castle, then you know how it feels to finish a Nick Harkaway book. It's like reading a giant magic trick where he spend the first 2/3 of the book showing you a bunch of only-vaguely-related things and then at the end they resolve into a story that becomes almost four dimensional.

It's a book that's entertaining, but has enough action, thoughtfulness, and sentiment to make it feel like something more than 'mere' scifi. And throughout it, Harkaway's writing manages to be the smartest kid in the room but somehow still likeable: big words, new words, sentences that roll on and on like friendly hills, characters who come alive in two or three words of description. It's the kind of thing anyone who likes to write will be able to appreciate, the way people who like dancing would want to watch ballet: it's intricate in detail and simple in execution.

I know I rave about Harkaway every time I mention him, but his books really deserve it. Anyone who likes science fiction should read at least one of his books. Probably more than once, because I really did enjoy this even more the second time around; I was able to focus more on the sidestories and little eddies of information, to think about the multi-leveled way the title works into the story (put it this way: more than one world disappears throughout the book.) This one was so good that as soon as it was done I thought about just starting it over from the beginning to go through it a third time. He's the only author I've ever written a fan letter to -- twice. (He's also the only author who I probably insulted when I left a comment on his Instagram where he was showing a banana bread he baked and I said at first I'd thought it looked like a slab of ground beef. I didn't mean it to be an insult. It's hard to get tone right in a comment on Instagram.)

There are things I like to do over and over in life. I like to go to the zoo, all the time. We have a free zoo in Madison. It's not very big, but it's big enough, and I go there about 4 times a year, even in winter. I like to go to the art museum over and over, too. Every year the boys and I go and wade up the river by the nature trail, swimming in the deep part and playing splash games. I do these things over and over because each time I do them they not only remind me of how great it was the last time I did them, but I get something new out of them again, and my enjoyment of them stretches back into the past to connect me with those earlier mes, but also stretched into the future, because of the knowledge that I will be doing this thing again sometime in the future, that future self of mine looking back on the present me and remembering each time how nice this thing was, and how I've enjoyed it so many times.

I've added reading Nick Harkaway books to that list.

Friday, June 03, 2016

A Conversation Amongst The Animals, At The Henry Vilas Zoo

|

| Hey, hey. Hey. Hey, polar bear. Hey! |

|

| WHAT?!?!?!?! |

|

| Do you believe in predestination? |

|

| Yeah. |

|

| No. |

|

| So you believe in free will then? |

|

| No, not really. |

|

| If you don't believe in predestination, then doesn't that automatically mean that we have free will? |

|

| Well? |

|

| They aren't necessarily opposites. Or the only choices. |

|

| How can that be? You just want to have it both ways. |

|

| I don't buy it. I believe in free will |

|

| I am my own bear. |

|

| You are the bear you helped make yourself, yes. |

Wednesday, June 01, 2016

Book 42: The more things change, the more I read old comic strips.

I didn't originally set out to read a collection of Doonesbury strips from the 1990s. It came about because Mr Bunches and I draw a lot of alphabets: he writes the letters and the words, I draw the pictures for him. In between pictures I have some down time, a minute or two. I would spend it chatting with Mr Bunches, but he is all business during alphabets so we can't talk about anything.

One night when we were down in the home office/playroom (Mr F wanted to swing in his hammock) Mr Bunches had me drawing the phonics alphabet, which is a long one. In between my pictures, I was glancing through The Portable Doonesbury, one of the several collections I have. As I read more and more I got kind of hooked on going through the 1990s and remembering issues that seemed big, and noting how much, or little, had actually changed.

Doonesbury is like a history book made funny and interesting. I first read the strip when I was about 11 or 12; the Hartland Library had a copy of Doonesbury's Greatest Hits on display, and I paged through it and then checked it out. I can still remember reading comics about "Park's Parking Tickets" and Duke's sojourn as governor of Samoa, and trying to piece together what these things meant. But even then I got the humor of the strip, in which the joke is almost always on society.

Since then I've been a huge fan of the comic, although it's been years since I went back to look at the old strips. Like I said, it was almost startling to remember things I hadn't thought of for years, and to realize that things don't change all that much.

This set of strips takes place roughly between the Kuwait war ("Operation Desert Storm," remember?) and Clinton being sworn in for his first term. It's not all politics; there are strips about performance art, which was kind of a big deal in the 1990s, especially when the National Endowment For The Arts became controversial.

It's not really clear when the culture wars began and politics began focusing so much on social issues, but looking back at this demonstrates how little lasting effect social issues can have. The NEA was created in 1965; Reagan promised to abolish it but conservatives (including Charlton Heston) convinced him not to. In 1989 it came under attack again for supporting controversial artists -- the infamous (and probably completely forgotten) Piss Christ was the genesis of this battle. It ended up in court, with the US Supreme Court holding that the law requiring the NEA to award its grants based only on artistic merit was constitutional, and awarding damages to four artists whose applications had been denied on the basis of subject matter. NEA funding has remained fairly consistent since 1990, surviving several recessions, and several extremely conservative congresses and presidents. It's still a favorite target of conservatives, though; fake conservative and failed VP candidate Paul Ryan suggested eliminating it in 2014. He failed.

The bulk of the book is taken up with Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm. I remember the outbreak of hostilities in that war; it was the first war in my lifetime. I watched blurry news photos of rocket attacks and wondered about my two friends who were in the Army and were over there.

Desert Storm was really the first incidence of a country renting our military; Saudi Arabia paid us $36,000,000,000 of the total cost (the total being estimated at $60,000,000,000.) The primary result of the whole operation would be the lessons learned by the government and military in 'sanitizing' war for the general population. The military's "pooling" of reporters meant that most news organizations had to rely on the government for their information and footage, which meant that the war featured fewer (or no) shocking images like Vietnam had.

The media policy, called "Annex Foxtrot," relied on claims of national security to censor the media and limit coverage. Sound familiar? The media didn't even fight back: Ted Koppel criticized the policy and networks wrote a strongly worded letter to the administration. I wasn't able to find a single report that anyone had challenged the policy in court. Such restrictions on media involvement are common now, and as a result, the war in Afghanistan has, on average, been given less than 2% of the total news coverage since it started.

In 2015 "the US reversed course and determined to maintain a combat presence in Afghanistan indefinitely." (Wikipedia.) This was roughly the fourth time the Obama administration had announced and then changed plans to "end" the war in Afghanistan. Obama's proposal now calls for the US to keep those troops there until 2017 (about 10,000 of them) at a cost annually of $15,000,000,000.

"Desert Storm" was, in retrospect, a remarkably short and restrained war. Bush I was criticized for stopping the troops short of Baghdad. Our 21st century leaders will never be accused of stopping a war.

The book also touches on one short-term political matter and one long-term. The short-term one was Dan Quayle, possibly the most memorable Vice President of the modern era. Quayle is mostly remembered for Murphy Brown and potatoe, and only one of those really mattered: The Murphy Brown claim that she was promoting unwed motherhood continued the rise of the conservative social issues that would ultimately find 'conservative' poor people siding with the Republicans against their own economic interests. (In a great article, Hamilton Nolan points out how Republicans, and to a lesser extent Democrats, use social issues to get the middle class and poor to vote them into power, with the rich who control the party using access to power to manipulate economic and political policy to keep the money flowing upward to the 1%.) (Access to power helps immensely. The Clintons had a net worth of about $700,000 when Bill was elected. Today they are worth $131,000,000.)

(Dan Quayle was worth "only" $1,000,000 when elected VP. Don't cry for him, Argentina: he has a 1/12 interest in a $600,000,000 family trust.)

In 1976, 41% of people with only a grade school education, or manual labor jobs, or both, voted for Ford. In 1980, Reagan and his Cadillac Welfare Queens for 42-48% of that demographic, and he got 49-54% of it in 1984.

In 1988 and 1992 and 1996, those trends reversed, with Democrats getting the vast majority of the manual labor/lowly educated people. The numbers then evened out for 2000 and 2004, then dropped again with Romney's race. A focus on social issues generally helped Republicans; in 1992 Clinton's campaign motto was "It's the economy, stupid," and he drove the debates in that direction -- resulting in fewer cultural-issue votes for Republicans.

Republicans tried to make character an issue throughout the 80s and 90s, but were far better at covering up their own problems than causing trouble for Democrats. Doonesbury spent a lot of time talking about Brett Kimberlin. Remember him? Nope. Almost nobody does. Kimberlin was a convicted drug dealer/bomber who prior to the election claimed to have sold marijuana to Dan Quayle; he scheduled 3 press conferences but each time was put into solitary before he could talk to the press. Although he was later discredited, a Senator in 1992 alleged that the Bush Administration had gotten Kimberlin thrown into solitary. Kimberlin is now a political activist and gets into frequent battles with conservatives.

Doonesbury was credited with forcing the release of the DEA file on Quayle. At one point, Gary Trudeau was picked as the 10th most influential person alive -- ahead of the Pope, but behind Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

The other ongoing storyline in this collection was the review of the Bush Administration's "oppo" research on Clinton -- a large team of people who were designated to dig up dirt on Clinton. A study found that lower-income people tend to believe negative advertising more than those with higher incomes; the same goes for education. Bush I was the candidate behind "Willie Horton," of course, and while it wouldn't be right to say he and his operatives were solely responsible for negative advertising's growth, he played a key role in it.

Doonesbury hit on just what was wrong with that type of operation when a character in the strip said to one of the "oppo" guys, Just imagine if that effort had gone into creating a domestic policy agenda.

History can sometimes be better learned through fiction. History isn't just the study of places and events and people. It's the study of interactions between events and people and places, and how they shaped our current life and systems. Events that seem momentous -- the NEA scandal -- end up having little to no impact ultimately. Events that seem minor -- government coverups of hyperbolic drug deals -- end up presaging a world in which two wars (and innumerable undocumented drone killings outside of war zones) are carried on with no media coverage and the government has over a million people who have a 'classified' ranking and know information the public cannot learn about.

Comics have never been so depressing.

One night when we were down in the home office/playroom (Mr F wanted to swing in his hammock) Mr Bunches had me drawing the phonics alphabet, which is a long one. In between my pictures, I was glancing through The Portable Doonesbury, one of the several collections I have. As I read more and more I got kind of hooked on going through the 1990s and remembering issues that seemed big, and noting how much, or little, had actually changed.

Doonesbury is like a history book made funny and interesting. I first read the strip when I was about 11 or 12; the Hartland Library had a copy of Doonesbury's Greatest Hits on display, and I paged through it and then checked it out. I can still remember reading comics about "Park's Parking Tickets" and Duke's sojourn as governor of Samoa, and trying to piece together what these things meant. But even then I got the humor of the strip, in which the joke is almost always on society.

Since then I've been a huge fan of the comic, although it's been years since I went back to look at the old strips. Like I said, it was almost startling to remember things I hadn't thought of for years, and to realize that things don't change all that much.

This set of strips takes place roughly between the Kuwait war ("Operation Desert Storm," remember?) and Clinton being sworn in for his first term. It's not all politics; there are strips about performance art, which was kind of a big deal in the 1990s, especially when the National Endowment For The Arts became controversial.

It's not really clear when the culture wars began and politics began focusing so much on social issues, but looking back at this demonstrates how little lasting effect social issues can have. The NEA was created in 1965; Reagan promised to abolish it but conservatives (including Charlton Heston) convinced him not to. In 1989 it came under attack again for supporting controversial artists -- the infamous (and probably completely forgotten) Piss Christ was the genesis of this battle. It ended up in court, with the US Supreme Court holding that the law requiring the NEA to award its grants based only on artistic merit was constitutional, and awarding damages to four artists whose applications had been denied on the basis of subject matter. NEA funding has remained fairly consistent since 1990, surviving several recessions, and several extremely conservative congresses and presidents. It's still a favorite target of conservatives, though; fake conservative and failed VP candidate Paul Ryan suggested eliminating it in 2014. He failed.

The bulk of the book is taken up with Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm. I remember the outbreak of hostilities in that war; it was the first war in my lifetime. I watched blurry news photos of rocket attacks and wondered about my two friends who were in the Army and were over there.

Desert Storm was really the first incidence of a country renting our military; Saudi Arabia paid us $36,000,000,000 of the total cost (the total being estimated at $60,000,000,000.) The primary result of the whole operation would be the lessons learned by the government and military in 'sanitizing' war for the general population. The military's "pooling" of reporters meant that most news organizations had to rely on the government for their information and footage, which meant that the war featured fewer (or no) shocking images like Vietnam had.

The media policy, called "Annex Foxtrot," relied on claims of national security to censor the media and limit coverage. Sound familiar? The media didn't even fight back: Ted Koppel criticized the policy and networks wrote a strongly worded letter to the administration. I wasn't able to find a single report that anyone had challenged the policy in court. Such restrictions on media involvement are common now, and as a result, the war in Afghanistan has, on average, been given less than 2% of the total news coverage since it started.

In 2015 "the US reversed course and determined to maintain a combat presence in Afghanistan indefinitely." (Wikipedia.) This was roughly the fourth time the Obama administration had announced and then changed plans to "end" the war in Afghanistan. Obama's proposal now calls for the US to keep those troops there until 2017 (about 10,000 of them) at a cost annually of $15,000,000,000.

"Desert Storm" was, in retrospect, a remarkably short and restrained war. Bush I was criticized for stopping the troops short of Baghdad. Our 21st century leaders will never be accused of stopping a war.

The book also touches on one short-term political matter and one long-term. The short-term one was Dan Quayle, possibly the most memorable Vice President of the modern era. Quayle is mostly remembered for Murphy Brown and potatoe, and only one of those really mattered: The Murphy Brown claim that she was promoting unwed motherhood continued the rise of the conservative social issues that would ultimately find 'conservative' poor people siding with the Republicans against their own economic interests. (In a great article, Hamilton Nolan points out how Republicans, and to a lesser extent Democrats, use social issues to get the middle class and poor to vote them into power, with the rich who control the party using access to power to manipulate economic and political policy to keep the money flowing upward to the 1%.) (Access to power helps immensely. The Clintons had a net worth of about $700,000 when Bill was elected. Today they are worth $131,000,000.)

(Dan Quayle was worth "only" $1,000,000 when elected VP. Don't cry for him, Argentina: he has a 1/12 interest in a $600,000,000 family trust.)

In 1976, 41% of people with only a grade school education, or manual labor jobs, or both, voted for Ford. In 1980, Reagan and his Cadillac Welfare Queens for 42-48% of that demographic, and he got 49-54% of it in 1984.

In 1988 and 1992 and 1996, those trends reversed, with Democrats getting the vast majority of the manual labor/lowly educated people. The numbers then evened out for 2000 and 2004, then dropped again with Romney's race. A focus on social issues generally helped Republicans; in 1992 Clinton's campaign motto was "It's the economy, stupid," and he drove the debates in that direction -- resulting in fewer cultural-issue votes for Republicans.

Republicans tried to make character an issue throughout the 80s and 90s, but were far better at covering up their own problems than causing trouble for Democrats. Doonesbury spent a lot of time talking about Brett Kimberlin. Remember him? Nope. Almost nobody does. Kimberlin was a convicted drug dealer/bomber who prior to the election claimed to have sold marijuana to Dan Quayle; he scheduled 3 press conferences but each time was put into solitary before he could talk to the press. Although he was later discredited, a Senator in 1992 alleged that the Bush Administration had gotten Kimberlin thrown into solitary. Kimberlin is now a political activist and gets into frequent battles with conservatives.

Doonesbury was credited with forcing the release of the DEA file on Quayle. At one point, Gary Trudeau was picked as the 10th most influential person alive -- ahead of the Pope, but behind Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

The other ongoing storyline in this collection was the review of the Bush Administration's "oppo" research on Clinton -- a large team of people who were designated to dig up dirt on Clinton. A study found that lower-income people tend to believe negative advertising more than those with higher incomes; the same goes for education. Bush I was the candidate behind "Willie Horton," of course, and while it wouldn't be right to say he and his operatives were solely responsible for negative advertising's growth, he played a key role in it.

Doonesbury hit on just what was wrong with that type of operation when a character in the strip said to one of the "oppo" guys, Just imagine if that effort had gone into creating a domestic policy agenda.

History can sometimes be better learned through fiction. History isn't just the study of places and events and people. It's the study of interactions between events and people and places, and how they shaped our current life and systems. Events that seem momentous -- the NEA scandal -- end up having little to no impact ultimately. Events that seem minor -- government coverups of hyperbolic drug deals -- end up presaging a world in which two wars (and innumerable undocumented drone killings outside of war zones) are carried on with no media coverage and the government has over a million people who have a 'classified' ranking and know information the public cannot learn about.

Comics have never been so depressing.

Tuesday, May 31, 2016

Update on Society: Just putting things in perspective.

From a Huffington Post story about the gorilla that was shot to protect a 4-year-old boy who fell into the enclosure. [My notes In Red]

The death of the gorilla, a 17-year-old Western lowland silverback named Harambe, outraged animal lovers, about 20 of whom staged a vigil outside the zoo. More than 200,000 people signed online petitions on Change.org to protest the shooting, some demanding “Justice for Harambe” and urging police to hold the child’s parents accountable.

The death of the gorilla, a 17-year-old Western lowland silverback named Harambe, outraged animal lovers, about 20 of whom staged a vigil outside the zoo. More than 200,000 people signed online petitions on Change.org to protest the shooting, some demanding “Justice for Harambe” and urging police to hold the child’s parents accountable.

2,370 people signed the Change.org petition urging the Wisconsin State Senate to reopen the investigation into the Madison police officer who shot a young man for no reason.

“The barriers are safe. The barriers exceed any required protocols,” Thane Maynard, director of the Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Gardens, said in answer to questions at a news conference about the incident on Saturday. “The trouble with barriers is that whatever the barrier some people can get past it. ... No, the zoo is not negligent,” he said.

2,464 people have been killed by US covert drone strikes done outside of war zones. No reporters asked Obama questions about that over the weekend.

Maynard, director of the Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Gardens, stood by the decision to shoot the gorilla after he dragged the boy around by the ankle. He said the ape was not simply endangering the child but actually hurting him.

“Looking back, we would make the same decision,” he said.

“The gorilla was clearly agitated. The gorilla was clearly disoriented,” said Maynard, while lamenting the loss of “an incredibly magnificent animal.”

One week ago, an 81-year-old woman ran over a 4-year-old boy after she took him from a daycare without permission. It's not known how the Zoo Director viewed this incident.

The zoo received thousands of messages of sympathy and support from around the world, he said.

Only 57.5% of US citizens voted in the last presidential election.

Animal lovers turned their anger toward the parents while mourning the death of the gorilla, lighting candles and holding “Rest in Peace” signs at the vigil.

“That child’s life was in danger. At the end of the day, it falls on the parents. No one else,” said Vanessa Hammonds, 27, who said she flew in from Houston to attend the vigil.

3 children were severely injured by accidental shootings in the Houston area on Memorial Day weekend, 2015. Guns are the number 2 cause of accidental deaths of children in the Houston area. It is not known how Ms. Hammonds feels about that.

Monday, May 30, 2016

Book 41: I mean you'd think a book with a French singer doing karaoke of a philosopher's poems after sucking caviar through a straw would be better than this, right?

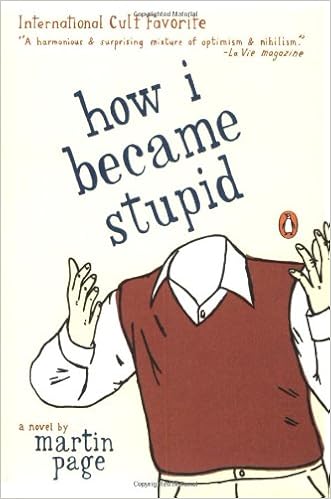

How I Became Stupid was the oldest book on my to-be-read list; I added it to my Amazon wishlist in June 2010, so it's been up there for about 6 years.

One of the reasons I stopped buying books in bulk, getting 2 or 3 or 4 at a time (aside from the sheer cost) was that by the time I get around to reading a book, I might not be in the mood to read it anymore. Some books have to hit me at the right time; I might think today that a book is going to be awesome but 6 months later my tastes have changed.

It's not just the passage of time that makes a book lose its luster. Sometimes a book that sits on a shelf for a while next to my bed will just start to seem like old news and I won't want to read it anymore. It's like they get stale. I can't really explain it.

So while I was reading How I Became Stupid, and to be honest not totally enjoying it, I was trying to think of what might have made me want to read it in the first place. At this point, 6 years on, I can't recall how I even first heard of the book.

How I Became Stupid is billed as an "International Cult Favorite," and promised hilarity and "coinage and invention." It's translated from French; the author is not the Martin Page who cowrote We Built This City, but some French guy.

The basic plot is a guy named Antoine decides that he's too smart and that his intelligence is getting in the way of his enjoying life. So he decides to make himself dumb. First he tries to become an alcoholic, then he decides to kill himself but chickens out after taking a class in suicide. Then he talks to a doctor about getting a lobotomy before getting a prescription for antidepressants. Taking a double dose of these leads him to like McDonalds and get a stock broker job. Once at that job, he twice spills coffee on his computer, and each time the short circuit causes a stock trade that makes him millions. He coasts in this job for a month or so before his old friend (who set him up with the job) tries to get him to go on a double-date with some escorts. At that point, Antoine's 'real' friends kidnap him and deprogram him with voodoo and Flaubert letters. Plus there's a visit from a ghost and, in the end, he meets a girl who makes him stand in the street until a car almost hits them, then pushes him aside and said she saves his life.

Aside from the intellectual snobbery of saying that people can be either smart or happy in modern life, and that dulling one's intellect is the only way to be happy, the book is mostly dull rather than offensive -- or 'inventive.' It feels almost like a mad lib plot, and while it touches on themes that are meant to feel significant, it rarely deals with them in either a thoughtful or entertaining way.

The best character in the book is a woman in a body cast. Antoine meets her when he tries his first beer and drops into an alcoholic coma after one sip; she is in the hospital because she keeps trying to commit suicide but fails. In her latest, she jumped off the Eiffel Tower and fell on some German tourists. I'd rather have followed her story than Antoine's.

The book tries to be madcap but mostly fails. One friend glows in the dark and can only speak in poetry, a quirk that might work better if the author had bothered to write a poem when the man spoke instead of just saying he was speaking in poetry. Antoine's aunt and uncle visit him in the hospital; they are patients there, too, and are convinced that the doctor has taken their spleens and replaced them with inferior spleens.

Antoine's awakening, or whatever, is accomplished without Antoine learning anything at all. I guess that was the point of the book, as Antoine announces in the beginning that his experiment in becoming stupid isn't intended to make him a better person.

But if you're going to write a book that wants to seem like it is asking a serious intellectual question about the role of intelligence vs. happiness, perhaps you ought to address the question? And if you're going to write a screwball intellectual comedy, like Jerry Lewis seen through Wes Anderson's eyes, you should make it funny and weird, instead of just a random assortment of things that seem designed to seem weird without the weirdness mattering.

It's a Potemkin village of a book, just a front of intellectualism and comedy with nothing real behind it. Ironically, it's exactly the kind of book that would be a cult hit in the world Page presents in the book: a world where people aren't smart enough to realize that things aren't as great as they think.

But in the real world, this book isn't worth waiting six minutes for, let alone six years.

One of the reasons I stopped buying books in bulk, getting 2 or 3 or 4 at a time (aside from the sheer cost) was that by the time I get around to reading a book, I might not be in the mood to read it anymore. Some books have to hit me at the right time; I might think today that a book is going to be awesome but 6 months later my tastes have changed.

It's not just the passage of time that makes a book lose its luster. Sometimes a book that sits on a shelf for a while next to my bed will just start to seem like old news and I won't want to read it anymore. It's like they get stale. I can't really explain it.

So while I was reading How I Became Stupid, and to be honest not totally enjoying it, I was trying to think of what might have made me want to read it in the first place. At this point, 6 years on, I can't recall how I even first heard of the book.

How I Became Stupid is billed as an "International Cult Favorite," and promised hilarity and "coinage and invention." It's translated from French; the author is not the Martin Page who cowrote We Built This City, but some French guy.

The basic plot is a guy named Antoine decides that he's too smart and that his intelligence is getting in the way of his enjoying life. So he decides to make himself dumb. First he tries to become an alcoholic, then he decides to kill himself but chickens out after taking a class in suicide. Then he talks to a doctor about getting a lobotomy before getting a prescription for antidepressants. Taking a double dose of these leads him to like McDonalds and get a stock broker job. Once at that job, he twice spills coffee on his computer, and each time the short circuit causes a stock trade that makes him millions. He coasts in this job for a month or so before his old friend (who set him up with the job) tries to get him to go on a double-date with some escorts. At that point, Antoine's 'real' friends kidnap him and deprogram him with voodoo and Flaubert letters. Plus there's a visit from a ghost and, in the end, he meets a girl who makes him stand in the street until a car almost hits them, then pushes him aside and said she saves his life.

Aside from the intellectual snobbery of saying that people can be either smart or happy in modern life, and that dulling one's intellect is the only way to be happy, the book is mostly dull rather than offensive -- or 'inventive.' It feels almost like a mad lib plot, and while it touches on themes that are meant to feel significant, it rarely deals with them in either a thoughtful or entertaining way.

The best character in the book is a woman in a body cast. Antoine meets her when he tries his first beer and drops into an alcoholic coma after one sip; she is in the hospital because she keeps trying to commit suicide but fails. In her latest, she jumped off the Eiffel Tower and fell on some German tourists. I'd rather have followed her story than Antoine's.

The book tries to be madcap but mostly fails. One friend glows in the dark and can only speak in poetry, a quirk that might work better if the author had bothered to write a poem when the man spoke instead of just saying he was speaking in poetry. Antoine's aunt and uncle visit him in the hospital; they are patients there, too, and are convinced that the doctor has taken their spleens and replaced them with inferior spleens.

Antoine's awakening, or whatever, is accomplished without Antoine learning anything at all. I guess that was the point of the book, as Antoine announces in the beginning that his experiment in becoming stupid isn't intended to make him a better person.

But if you're going to write a book that wants to seem like it is asking a serious intellectual question about the role of intelligence vs. happiness, perhaps you ought to address the question? And if you're going to write a screwball intellectual comedy, like Jerry Lewis seen through Wes Anderson's eyes, you should make it funny and weird, instead of just a random assortment of things that seem designed to seem weird without the weirdness mattering.

It's a Potemkin village of a book, just a front of intellectualism and comedy with nothing real behind it. Ironically, it's exactly the kind of book that would be a cult hit in the world Page presents in the book: a world where people aren't smart enough to realize that things aren't as great as they think.

But in the real world, this book isn't worth waiting six minutes for, let alone six years.

Sunday, May 29, 2016

Book 40: Just some more rambling about Xanth nothing to see here move along.

It's really kind of remarkable what Piers Anthony has done with Xanth. He's created a fantasy series in which there's action and brain-teasers, but the silly puns and lighthearted nature of the book belies the seriousness of some of the scenes. For example, when I first sat down to write this I was going to say that there's no real horror to the battle scenes, nothing grim or epic in Xanth the way there is in Middle Earth, say, or even Narnia, to take a lighter-hearted example.

But that's not true, entirely: In one of the books there's a siege of Castle Roogna, and there are deaths galore, as well as a pitched battle involving vampires, goblins, harpies, zombies, soldiers, and a giant spider.

(Giant spiders seem to be a staple in fantasy books: Harry Potter, The Lord of The Rings, and Xanth have all had one. I can't remember one in Narnia but that doesn't mean there wasn't one.)

The lighthearted feel of Xanth is, though, in stark contrast to most of fantasy writing that's out there. I think that (plus Anthony's admittedly somewhat simple writing style) causes many people to downgrade or disregard the series -- or to honestly dislike it the way Andrew Leon does -- because while there are epic quests and horrible deaths and demons and the like, it's all portrayed in a sort of Saturday morning cartoonish feel.

The Color Of Her Panties continues that combination of quests-and-kids-stuff feeling, as a former side character, Mela the Merwoman, decides to go find a husband, and ends up joining forces with a dissatisfied ogress, a mystery human woman, and some teenage folk who have to help a friend take over as a chieftain of the goblins. What got me started on thinking about where Anthony might fit in the pantheon of fantasy writers was a couple of things.

First, early on in this book Anthony essentially undoes an entire plotline from the earlier books. The main plot here is Gwenny Goblin having to finally take over as chief of her mountain. In an earlier book, Gwenny's mom kidnapped a winged centaur to help Gwenny, who was crippled and nearly blind; that set off a war between the winged monsters and the land monsters, but was eventually settled with the sort of almost-deus ex machina that Anthony favors as an ending to his books; the centaur decided to be Gwenny's companion to help hide her infirmities.

At the start of this book, Gwenny has had her lameness cured by a healing spring, and she recovers a pair of magic contact lenses to help her see, so she doesn't need the winged centaur anymore and the entire book leading up to this became unnecessary. It's not clear if Anthony simply didn't care, or is on a larger path with these. Lots of times what seems to be simple throwaway stuff ends up mattering in later books, but again, the tone of the books keeps them from seeming as literary as some other fantasy.

The other thing that got me thinking about Anthony's skills was the Simurgh, which in Xanth is a bird that sits atop a tree on Mount Parnassus and occasionally dispenses wisdom. The Simurgh has been in enough books that I finally decided to see if Anthony had just made it up, because it's kind of a neat creature, having lived through three universes so far and being able to see at least part of the future.

Turns out there really was a Simurgh, at least in our mythology: it was an Iranian god that, while not quite fully a bird, was similar to the one Anthony has repurposed for his books. Anthony already has Maenads on Mount Parnassus, too, and the more you dig into Xanth the more you find bits and pieces of mythology sprinkled around amongst the pie plants.

Those pie plants and the other fun stuff of Xanth led me to decide, when we were debating it one time, that if I could live in any literary world, it would be Xanth. Harry Potter's got his dementors and Voldemorts. Middle Earth sounds horrible unless you live in Rivendell or are a king of Gondor, or maybe a hobbit provided you're not there when Sharkey takes over. Most other fantasy worlds, too, are hard-scrabble, rainy, plagued with enemies (and plagues) and otherwise not worth living in.

Anthony's worlds are different. Phaze, his fantasy/scifi world in Split Infinity seems awesome, and even the Earth he posits in his Incarnations of Immortality series seems generally okay. But Xanth is by far the greatest of his creations, should you have to go live in a literary fantasy world.

This book, too, sees Anthony mess with the fourth wall. The ogress, Okra Ogress, wants to be a Major Character, because nothing bad ever happens to Major Characters. (That's true, in Xanth: in the last invasion all the kings who were dispatched simply went to the dreamworld for a while, then came back to life.) Okra wasn't a major character because Jenny The Elf got the job, instead; this is of course a nod to the book where Anthony put a real-life girl into his stories as an Elfquest elf, after having given her the choice of being an elf or an ogress.

This isn't the first time Anthony has done something like that. In Man From Mundania he had Grey, the Mundane Magician, read books about Xanth that were written by the Muses on Mount Parnassus and snuck out; here he makes it more overt, even having Jenny and Grey read his Author's note.

I think one of the reasons why I'm enjoying these Xanth books so much (sorry, Andrew) is because they seem so innocent. Like I said last time, they're some lighter reading that I can sort of drift along with, but they're entertaining enough to make me want to keep going. And I like that as they go along Anthony is making the stories a bit more complicated, bringing in new characters (especially nonhumans; there's not a lot of those starring in the fantasy books I've read, and while Anthony's nonhumans are mostly a lot like humans, he sometimes makes it really interesting, like the book Night Mare, told from the perspective of a dream horse.)

I think it's possible that Tolkien and Martin and Rowling are rated so highly because they paint their fantasy worlds in grim colors, blood and iron and boiling lava. That's very entertaining, but downgrading lighter fantasy like Narnia, or Robert Asprin's Myth series or Xanth simply because they're lighthearted is wrong. If you don't like them you don't like them; taste is subjective. But I think the Xanth books ought to be given more credit in the fantasy community than they seem to get.

But that's not true, entirely: In one of the books there's a siege of Castle Roogna, and there are deaths galore, as well as a pitched battle involving vampires, goblins, harpies, zombies, soldiers, and a giant spider.

(Giant spiders seem to be a staple in fantasy books: Harry Potter, The Lord of The Rings, and Xanth have all had one. I can't remember one in Narnia but that doesn't mean there wasn't one.)

The lighthearted feel of Xanth is, though, in stark contrast to most of fantasy writing that's out there. I think that (plus Anthony's admittedly somewhat simple writing style) causes many people to downgrade or disregard the series -- or to honestly dislike it the way Andrew Leon does -- because while there are epic quests and horrible deaths and demons and the like, it's all portrayed in a sort of Saturday morning cartoonish feel.

The Color Of Her Panties continues that combination of quests-and-kids-stuff feeling, as a former side character, Mela the Merwoman, decides to go find a husband, and ends up joining forces with a dissatisfied ogress, a mystery human woman, and some teenage folk who have to help a friend take over as a chieftain of the goblins. What got me started on thinking about where Anthony might fit in the pantheon of fantasy writers was a couple of things.

First, early on in this book Anthony essentially undoes an entire plotline from the earlier books. The main plot here is Gwenny Goblin having to finally take over as chief of her mountain. In an earlier book, Gwenny's mom kidnapped a winged centaur to help Gwenny, who was crippled and nearly blind; that set off a war between the winged monsters and the land monsters, but was eventually settled with the sort of almost-deus ex machina that Anthony favors as an ending to his books; the centaur decided to be Gwenny's companion to help hide her infirmities.

At the start of this book, Gwenny has had her lameness cured by a healing spring, and she recovers a pair of magic contact lenses to help her see, so she doesn't need the winged centaur anymore and the entire book leading up to this became unnecessary. It's not clear if Anthony simply didn't care, or is on a larger path with these. Lots of times what seems to be simple throwaway stuff ends up mattering in later books, but again, the tone of the books keeps them from seeming as literary as some other fantasy.

The other thing that got me thinking about Anthony's skills was the Simurgh, which in Xanth is a bird that sits atop a tree on Mount Parnassus and occasionally dispenses wisdom. The Simurgh has been in enough books that I finally decided to see if Anthony had just made it up, because it's kind of a neat creature, having lived through three universes so far and being able to see at least part of the future.

Turns out there really was a Simurgh, at least in our mythology: it was an Iranian god that, while not quite fully a bird, was similar to the one Anthony has repurposed for his books. Anthony already has Maenads on Mount Parnassus, too, and the more you dig into Xanth the more you find bits and pieces of mythology sprinkled around amongst the pie plants.

Those pie plants and the other fun stuff of Xanth led me to decide, when we were debating it one time, that if I could live in any literary world, it would be Xanth. Harry Potter's got his dementors and Voldemorts. Middle Earth sounds horrible unless you live in Rivendell or are a king of Gondor, or maybe a hobbit provided you're not there when Sharkey takes over. Most other fantasy worlds, too, are hard-scrabble, rainy, plagued with enemies (and plagues) and otherwise not worth living in.

Anthony's worlds are different. Phaze, his fantasy/scifi world in Split Infinity seems awesome, and even the Earth he posits in his Incarnations of Immortality series seems generally okay. But Xanth is by far the greatest of his creations, should you have to go live in a literary fantasy world.

This book, too, sees Anthony mess with the fourth wall. The ogress, Okra Ogress, wants to be a Major Character, because nothing bad ever happens to Major Characters. (That's true, in Xanth: in the last invasion all the kings who were dispatched simply went to the dreamworld for a while, then came back to life.) Okra wasn't a major character because Jenny The Elf got the job, instead; this is of course a nod to the book where Anthony put a real-life girl into his stories as an Elfquest elf, after having given her the choice of being an elf or an ogress.

This isn't the first time Anthony has done something like that. In Man From Mundania he had Grey, the Mundane Magician, read books about Xanth that were written by the Muses on Mount Parnassus and snuck out; here he makes it more overt, even having Jenny and Grey read his Author's note.

I think one of the reasons why I'm enjoying these Xanth books so much (sorry, Andrew) is because they seem so innocent. Like I said last time, they're some lighter reading that I can sort of drift along with, but they're entertaining enough to make me want to keep going. And I like that as they go along Anthony is making the stories a bit more complicated, bringing in new characters (especially nonhumans; there's not a lot of those starring in the fantasy books I've read, and while Anthony's nonhumans are mostly a lot like humans, he sometimes makes it really interesting, like the book Night Mare, told from the perspective of a dream horse.)

I think it's possible that Tolkien and Martin and Rowling are rated so highly because they paint their fantasy worlds in grim colors, blood and iron and boiling lava. That's very entertaining, but downgrading lighter fantasy like Narnia, or Robert Asprin's Myth series or Xanth simply because they're lighthearted is wrong. If you don't like them you don't like them; taste is subjective. But I think the Xanth books ought to be given more credit in the fantasy community than they seem to get.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)